Black youth experience high unemployment

Metro Unemployment

February 1, 2016

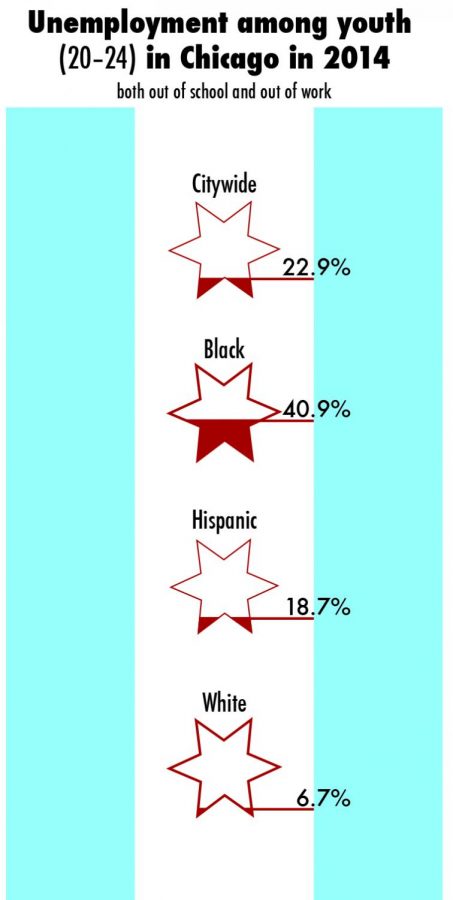

Nearly half of young, African Americans in Chicago are jobless and out of school, according to a new youth unemployment report that shows Chicago to be far worse at keeping young people off the streets than other major cities.

The study, commissioned by the Alternative Schools Network, a nonprofit organization that provides education for inner city youths, and prepared by the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Great Cities Institute, which conducts urban research, looked at 20- to 24-year-olds in Chicago in 2014 and found that 40.9 percent of black youths are out of school and work.

In New York, that number is 27.3 percent and in Los Angeles it is 29.3 percent, according to the report.

While black youths struggle disproportionately to receive education or find part-time employment, according to the report, Hispanic youths in Chicago fare somewhat better with only 18.7 percent in that category, By contrast only 6.7 percent of white youths lack jobs and educational opportunities.

“This has gone on for a long period of time,” said Teresa Cordova, director of the Great Cities Institute. “It’s more than just a momentary problem.”

According to Cordova, a lack of commercial and manufacturing opportunities in hard-hit neighborhoods on the city’s South and West sides is at the root of staggering unemployment rates, adding that it creates a cycle of joblessness and criminal behavior.

“There is a definite relationship between these communities that are highly segregated and places where there is low employment,” Cordova said. “If we’re going to address these issues, we need to address what’s happening in the neighborhoods themselves.”

Cordova said the situation is most severe for 20- to 24-year-old black males, 46.7 percent of whom are jobless, according to the report.

Jack Wuest, executive director of the Alternative Schools Network, said he hopes people will see studies like this one and take action by working to bring jobs to affected communities.

“It’s a huge burden for them because they can’t make much of a living,” Wuest said. “It’s a huge burden for society because it leads to violence and guys working on the streets and getting arrested for different nonviolent crimes.”

Wuest said a lack of work opportunities in these neighborhoods leads to an uptick in crime that in turn triggers higher health care, prison and welfare costs assessed on the public through taxes.

“Kids in the inner city, those neighborhoods have been destroyed,” Wuest said.

A study conducted in 2012 by the University of Chicago Crime Lab, where at-risk youth from deteriorating and crime-ridden neighborhoods were offered spots in an eight-week summer jobs program in government and nonprofit positions, found that participants experienced a 43 percent drop in arrests for violent crime.

The program, One Summer Plus, provided participants with mentors to help support them through their new workload.

“People have thought for a long time that it makes sense that a job would be important to avoid violence,” said Kelly Hallberg, the scientific director of the U of C Crime Lab who conducted the study. “Until we did this work, there wasn’t a lot of very strong evidence that showed the connection between offering a job and the reduction in violence.”

Cordova said results of reports like hers and the one conducted by Hallberg are hard to ignore.

“The report really confirms what we know and what people who are living this reality know,” Cordova said.