Exhibit puts juvenile prisoners on display

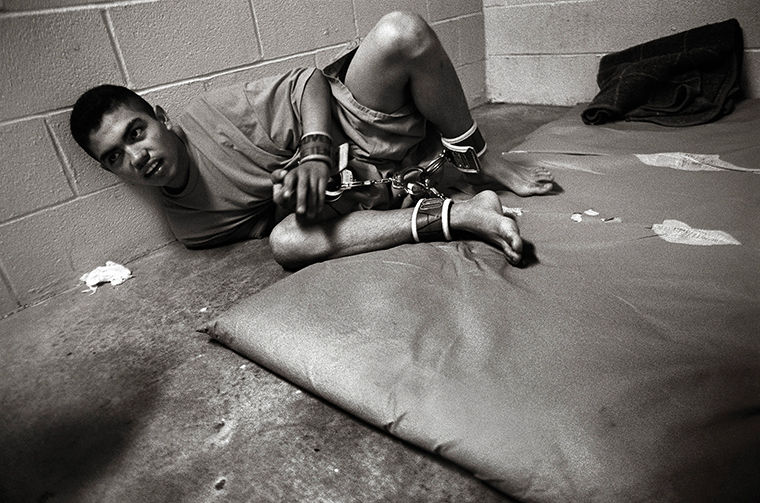

“Voices From Juvenile Detention: Kids Behind Bars” It sounds harmless: “pre-trial detention.” But the reality is far different. In a squat block building in Laredo, Texas—and in similar places around the nation—children await trial or placement in concrete cells while the underlying issues that led to their behavior fester. Some are addicts who need treatment; others are kids battling mental illnesses. Many are angry and have been virtually abandoned by absentee or irresponsible parents. Some spend a few days, others months, but despite the efforts of a small corps of dedicated professionals, few actually receive treatment for the issues that brought them to Juvenile. /// 15-year-old Gabriel, restrained while he detoxes in a cell at Webb County Juvenile Detention. “How I got here? I don’t remember, sir.” Gabriel, 15, took 10 rRohypnol pills (a potent tranquilizer) and boarded the bus to school. Stoked by the drugs, an argument with another kid turned ugly. A teacher who intervened says Gabriel threatened him. When he arrived in Juvenile–his fifth time there–officers found more pills in his pocket. He is charged with “possession of a controlled substance in a correctional facility”–a felony. And Gabriel isn’t the only child brought to Juvenile in a narcohaze. Far from it, according to Jesse Hernandez, head of a local drug counseling program: “Virtually everyone in the juvenile detention system is abusing drugs or is dependent. At one point, Doctor’s Hospital had opened up the mental health unit and we had an adolescent detox here. In 2002 we had to give it up because it’s very cost-prohibitive to run a program like that. Unfortunately, a lot of kids are now having to be detoxed in the detention center. . . . “You never want to get in a situation where you’re having to restrain people who are under the influence. It’s dangerous.

April 27, 2015

“Try Youth As Youth,” an exhibit that aims to spark social change, highlights the lives and trials of American youth in juvenile detention centers across the U.S.

“Try Youth As Youth” is a project spearheaded by the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois in partnership with David Weinberg Photography, according to Ed Yohnka, director of communications and public policy for the ACLU of Illinois. The exhibit is being held at David Weinberg Photography, 300 W. Superior St., and is meant to put human faces to the numerous young adults in juvenile detention centers in the hopes of creating a conversation for change and a better way to deal with young offenders.

Yohnka said the project grew out of a longtime relationship between the ACLU and David Weinberg Photography. He said both organizations wanted to speak out about what is happening with American youth and juvenile detention centers because they believe there could be a better way to deal with these issues.

“It was fascinating in many ways to think about how the use of images could be part of the storytelling and the narrative of social justice movements overall,” Yohnka said. “If you look at the state of Illinois as an example, we move these people to a remote part of the state and then we hope that we forget about them. We never have to confront the consequences of our policies.”

Yohnka said the exhibit’s aim is to highlight the harsh realities of how society views these young boys and girls and the policies that place them in the detention centers where they reside.

“Our criminal justice policies … have effectively been built around the notion that we are protecting ourselves by putting these kids away,” Yohnka said. “When you really look at those photos and read these stories, you begin to realize that what you’re really talking about are children.”

Steve Davis, a photographer whose work from his book, “Captured Youth,” is featured in “Try Youth As Youth,” said he got involved with documenting youth detention centers on the West Coast through an educational program that brought artists to the centers to teach workshops for the detained youth. Davis said he started teaching the workshops in the mid-‘90s and began taking photos inside the facilities.

“At the very beginning, there was a clear agenda of what I was doing and what the kids were doing,” Davis said. “Not just my workshop, but all of these artists’ workshops would become a book, a catalogue basically, and a touring exhibit that went into the Seattle school district in some of the more at-risk populations. The message the kids and me as well were trying to get across is, ‘You don’t want to be here, this is what you want to stay away from.’”

Davis said the work he produced while working in detentions centers would lead to advocacy for the kids who were imprisoned—something he said he really had not expected when he began the project.

“I don’t think I really understood what I was doing or who was even going to care, that just was not clear to me, but I was very intrigued by it, not just because they were incarcerated, but the idea of being institutionalized, where basically the state becomes your mother figure,” Davis said.

Steve Liss, a longtime photographer for Time magazine and a former professor of photography at Columbia, whose photographs from his book, “No Place For Children,” are featured in the exhibit, participated in “Try Youth As Youth” after fellow photographer Carlos Ortiz introduced him to David Weinberg Photography. Liss said he was not pleased with the outcome of the exhibit because he did not think the subjects of the photos were meant to be art.

“[There’s] an exploited nature to it, these kids are not art,” Liss said. “They don’t belong in a gallery, they don’t belong in a museum. These are real lives and real people who have entrusted me to tell their story, and I don’t want people with opera glasses and a monocle to come in and say, ‘Oh, look at the light and the lines,’ that’s bulls–t, I’m very clear that I don’t want to work with a gallery ever again.”

Liss, whose work in the exhibit dates back to the time he spent photographing a juvenile detention center in Laredo, Texas, said it was his intention to take the photographs in order to produce a conversation for social change, something he said the exhibit would not accomplish.

“I don’t think this is an effective way to bring about a social change,” Liss said. “I think all too often you are preaching to the choir, those who probably agree with everything they see and are probably shocked by it, but the question in my post-Time magazine life is I have been trying to use media to stimulate [is] to advocate social change, and I don’t think this is an effective way to do it.”