Survey shows Columbia full-time faculty dissatisfied with college penny pinching

October 29, 2018

A survey conducted by the Columbia Faculty Senate shows faculty members are more dissatisfied with the college compared to last year’s survey, particularly with regard to compensation, the administration and its policies. Yet, the survey reports most faculty members are not seeking new employment.

The survey is in its second year, the first iteration conducted in 2017. The results of the survey are preliminary and pending revision by the faculty affairs committee.

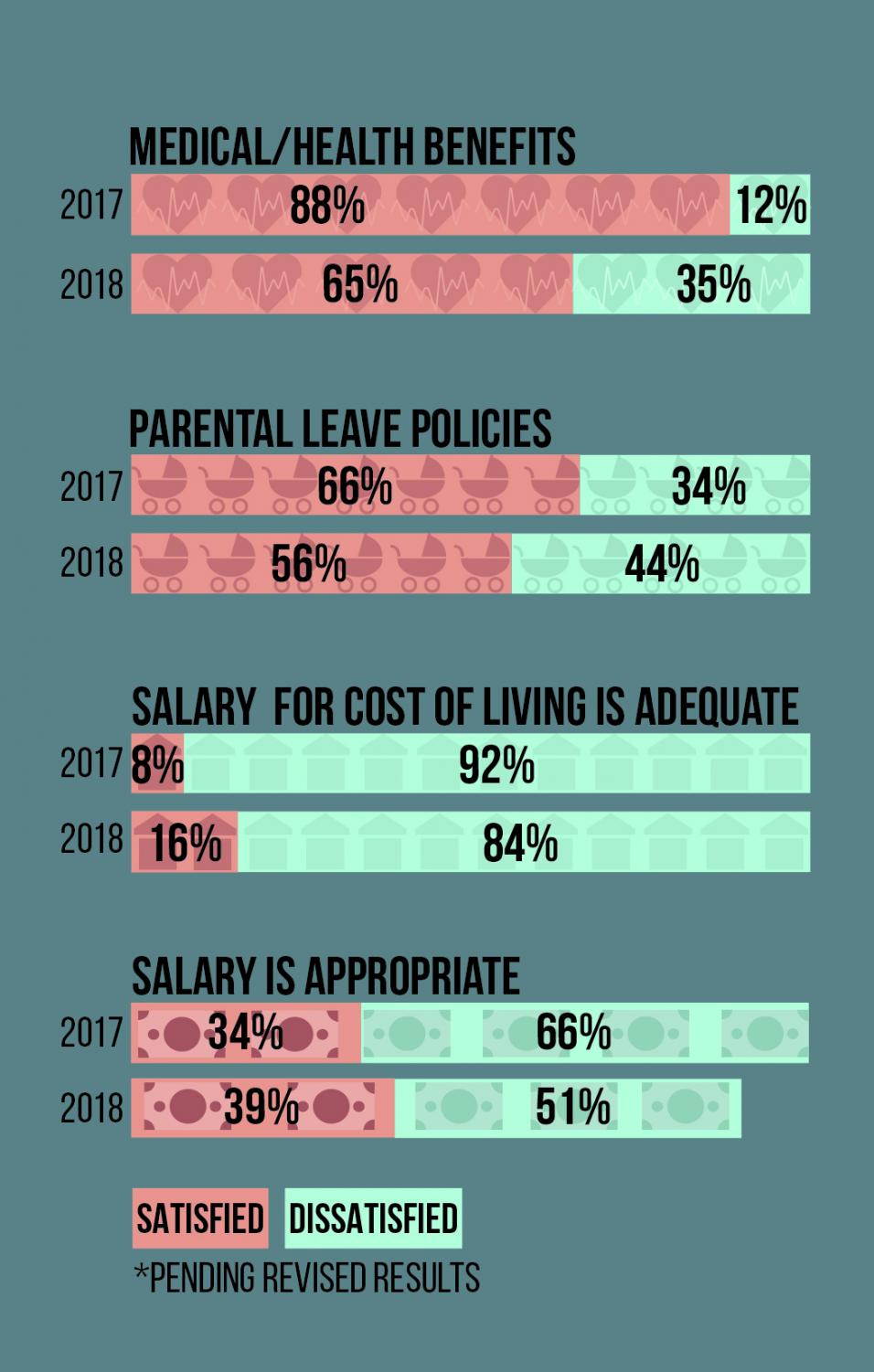

Sixty-five percent of the 191 respondents reported being satisfied with medical and health benefits, a decrease from last year’s survey, which reported 88 percent of respondents being satisfied.

“There have been changes to the healthcare benefits recently, and there are changes coming up,” said Sean Andrews, associate professor in the Humanities, History and Social Sciences Department and Faculty Senate president. “There’s going to be an increased amount faculty have to pay for their monthly premium. We’re still getting a better deal than some other institutions, but it’s a worse deal than we had before.”

Fifty-one percent of respondents said they disagreed with the value of their current salary, a decrease from last year’s survey which reported 66 percent of respondents disagreeing with the appropriateness of their salary. Sixteen percent of respondents agreed their cost-of-living adjustments were adequate, following years of no cost-of-living adjustments by the college.

Senior Vice President and Provost Stan Wearden said the dissatisfaction comes from budget cuts due to low enrollment.

“Faculty are beginning to feel like their compensation, in spite of these efforts, may not be keeping up in ways they had hoped,” Wearden said. “We want to make sure we have competitive salaries to attract and retain good faculty.”

Wearden said the college is currently engaged in a deep-dive analysis of Columbia faculty salaries compared to other higher education institutions to see if the college is in line with the market.

The college decided several years ago not to do a cost-of-living increase and instead do performance-based compensation increases, Wearden said. However, Andrews said those increases are not enough.

The survey also reported only 24 percent of respondents were satisfied with the administration’s implementation of college policies; 58 percent said they were satisfied with salary equity adjustment policies but only 38 percent reported being satisfied with the way changes in college policies and leadership were communicated.

About 56 percent reported being satisfied with parental leave, which is a 10 percent decrease compared to last year.

“To say faculty have a problem with parental leave policies is to say we have a parental leave policy, but we really don’t,” Andrews said. “We have the bare minimum, as required by the federal government, which is just to say you’re allowed to take [unpaid] time off and not get fired.” Andrews also said it was demoralizing for administrators to create or change policies without including faculty in the process.

However, Wearden said he makes a personal effort to connect with Faculty Senate on a regular basis in order to increase communication.

Sixty-six percent of faculty reported being dissatisfied with administrative leadership, including with the Office of Academic Affairs and the provost.

Wearden said these numbers can be due, in part, to the social distance effect, wherein the further in rank respondents are from the person they are reviewing, the worse their rating. Wearden encouraged faculty to get involved with Faculty Senate in order to have their concerns heard and acted upon.

Andrews did not attribute dissatisfaction to the distance.

“We are in a time when there’s a great deal of turnover at the level of deans and chairs—and now even the provost—and that kind of uncertainty and change in leadership happening periodically and suddenly makes it difficult to have confidence in the leadership,” Andrews said.

And yet, 70 percent of respondents said they are satisfied being a full-time faculty member at the college, and only 36 percent said they intended to leave Columbia in the near future. Wearden said the satisfaction comes from the unique student-professor relationship and creative atmosphere Columbia offers.

Although Andrews said he and his colleagues love working at Columbia for the reasons Wearden cited, that satisfaction may change depending on how the administration acts in the future.

Assistant Professor of higher education at the University of Massachusetts Boston Ray Franke said Columbia’s survey pales in comparison to other institutions’ because it is not as comprehensive or broken down demographically by rank, gender or age.

“You find through some of these questions where it’s superficially scratched on, like ‘overall satisfaction’ or ‘happiness with salary,’” Franke said.

In the future, Franke said the college should consider implementing focus groups instead because they are more effective and provide a deeper analysis of faculty sentiment through discussion of issues.

Andrews said he has not seen any interest from senior administrators in the results of the survey, adding that he has been told college administration has no short-term plans to make changes to address concerns reported on the survey.

“We’re entering a period when there will be tough decisions the administration has to make,” Andrews said. “It would be good if the faculty were involved in those decisions, so that if they do impact the curriculum, the faculty will continue to feel like it is a good institution.”