Illinois falls behind nation in STEM gender equity

Gender Equity in STEM Education

February 23, 2015

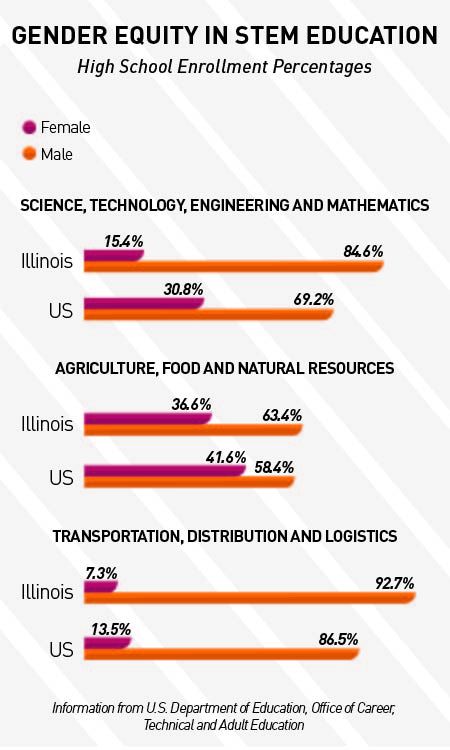

Despite the launch of President Barack Obama’s “Educate to Innovate” initiative in late 2009—an effort made to expand science, technology, engineering and math education and exposure to students—enrollment in STEM coursework is still significantly higher among male students than females. New research from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign reveals that the gender gap is even greater in Illinois, where only 15.4 percent of high school girls are enrolled in STEM courses, compared to 30.8 percent nationwide.

“[The gap may exist because] females may not have considered a career in STEM or they may not—at home or through other popular media—have seen themselves [represented] in STEM-related fields,” said Donald Hackmann, a co-author of the study and an Education Policy, Organization and Leadership professor at U of I. “I think helping females to be more aware of the opportunities that are available to them is a really good approach. There’s a lot of societal expectations that we are still dealing with and will still continue to deal with unless we carefully and overtly address these concerns.”

U of I’s Pathways Resource Center, which provides resources to students and school districts, released the study. Hackmann, the director of the Pathways Resource Center, and co-authors Joel Malin and Asia Fuller Hamilton, compiled Illinois State Board of Education data and career and technical education enrollment information from the U.S. Department of Education.

“We feel that having a diverse workforce with individuals from different genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, we feel that ultimately, that will make our economy stronger, and that [is] ultimately what we should shoot for,” Malin said. “We want to make sure each career area, each possible avenue for students or for adults, can be pursued by individuals from all different backgrounds. We feel that will be a good thing for our society.”

The study included recommendations and strategies for state policymakers to eliminate the gender gap such as improving data collection systems for more transparent reviews, as well as providing incentives to school districts that are successful at increasing female enrollment in traditionally male-dominated fields.

“We feel there are a number of things that educators can do as well,” Malin said. “We’ve been highlighting some of the things that are happening around the state, for example, putting on conferences so that they can be exposed to other areas and see what their interests might be. Things like summer bridge programs can make a big difference, and having non-traditional role models who can come in and talk about what they’re doing and what their job entails. We think these are some of the things that can make a big difference.”

According to Hackmann, school districts should also ensure they are encouraging female enrollment in STEM coursework.

“As school officials look at their programs, consider their practices as well [to ensure they are not] doing anything that may be discouraging females from considering careers in STEM fields,” Hackmann said. “It may not be overt. It may be simple things like materials that students are looking at. Are females represented in materials as well so they can see there is a role for them in STEM fields? Little things [like that] may increase access and female awareness and understanding that the STEM fields may be something for them.”

University-supported programs such as the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Women in Science and Engineering Program work to encourage and empower girls to consider STEM career paths and college majors, according to WISE Program Director Veronica Arreola. Through WISE’s pre-college program, UIC students and faculty work with girls in the Chicago area through outreach programs and mentorships to provide support for female students who are interested in science and engineering. The disparity can be attributed to science’s perception in media and society, according to Arreola.

“Our society does a pretty poor job of talking [about] what scientists and engineers do,” Arreola said. “I think there’s a misunderstanding as to what that means. This pushes us to rely on stereotypes like the mad scientist with the crazy hair and the white lab coat and the glasses being in a laboratory by himself, usually male. That’s the purpose of our outreach program—to get out there and break some stereotypes.”

The gap in achievement on standardized tests, such as the ACT and SAT, is much more narrow between boys and girls, although a disparity in course enrollment remains, according to Arreola.

“More boys are taking physics and more girls are taking biology-type courses, especially when you look at AP courses,” Arreola said. “I think that’s something that schools need to address. I don’t think schools should just simply say, ‘Well, the boys are choosing that and the girls are choosing that.’ I asked a high school teacher once and they were like, ‘That’s just what happens.’ I think we need to stop saying that’s just what happens and inquire what’s going on there.”