A mother’s story: reliving the shooting scene

May 9, 2016

When a doorbell rings in the dead of night in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, hearts leap into throats and mothers panic; it can’t be good.

In the early hours of Jan. 7, 2011, Gloria Pinex received an unexpected visitor. She had been waiting for her son, Darius Pinex, to come home from visiting his child’s mother’s house, where he was planning his 11-year-old daughter’s birthday party scheduled for the next day.

From the other side of the front door, a friend of Darius’ said, “Darius is dead.”

Dressed in her pajamas, Gloria Pinex did not let her son’s friend into her house.

“Just like that, Darius [is] dead,” she said in her living room five years later, as she recalled for The Chronicle what happened the night her 27-year-old son was shot and killed by Chicago police officers Raoul Mosqueda and Gildardo Sierra.

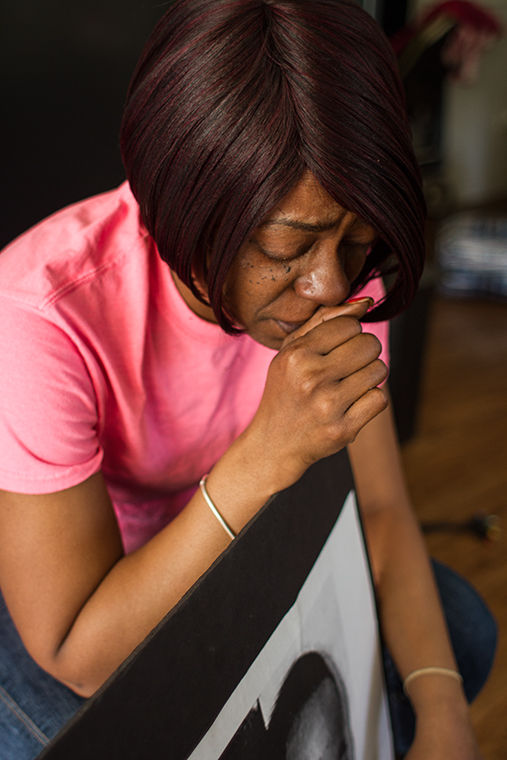

“I did not want to go out [to the shooting scene],” she said, holding a black-and-white portrait of her son. “I was hoping and praying that [it was not my son], but it was him.”

Darius Pinex is only one of the 299 black people who have been shot and in many cases slain by Chicago police from 2008–2015, according to the Police Accountability Task Force report published in April. Despite the city being almost evenly distributed demographically among black, white and Hispanic individuals, black Chicagoans were most likely to be involved in police shootings.

Of the 404 police-related shootings in this period, only 55 victims were Hispanic and just 33 were white.

Cases similar to Pinex’s—such as that of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown, who was shot and killed by police officer Darren Wilson in August 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri, and black teenager Laquan McDonald, who was shot 16 times and killed by police officer Jason Van Dyke in Chicago on Oct. 20, 2014—have been thrust into the national spotlight precipitating movements like #BlackLivesMatter.

Christopher Donner, assistant professor in the Criminal Justice & Criminology Department of Loyola University Chicago, said people often cite racial minorities’ statistics in terms of their representation in the criminal justice system compared to their representation in the population.

“One statistic often thrown out is that [black Americans] make up about 13 percent of the country and about 40–45 percent of the criminal justice population,” Donner said.

On a national scale, 990 Americans were shot dead by police in 2015; of these, 258 or 26 percent were black, according to the Washington Post’s database.

Gloria Pinex filed a lawsuit against the city, lost the case and has now been granted a second trial scheduled for July 18 after Judge Edmond Chang found that city lawyers intentionally withheld evidence or failed to properly search for evidence.

As she further recalled details of the scene, she gripped the portrait tighter and tears ran down her cheeks.

When Gloria and her mother arrived at the scene at 1119 W. Marquette Road, the area was bustling with police cars and curious neighbors, onlookers and friends, who attempted to reassure her that the police had yet to identify the body and that they hoped it was not Darius.

But Gloria said she knew it was her son who had died. She recognized his car, a 1998 green Oldsmobile Aurora, parked in the middle of the street surrounded by yellow tags and a taped crime scene.

“My mother wanted to tear the tape down [to see him],” Gloria said. “I had to stop my mother before they shot [her] as well.”

Gloria said she stood at the scene for hours waiting for an explanation from the police.

“They never told me [it was my son],” Gloria said. “Not one police officer told me anything.”

Gloria said WGN reporter Judy Wang officially broke the news of Darius’ reported death to her at about 3 a.m. when pursuing an interview with her at the scene.

Gloria said she was determined to stay at the scene until she could see her son.

“They tried to tell me that he was no longer there,” she said. “I knew they [were] lying.”

Gloria said she watched the forensics team pull her son’s body out of his car.

They laid him on the ground to examine his wounds: one gunshot wound in the right ear and two others in the right upper arm, which left multiple holes in his black jacket and T-shirt, according to his autopsy report.

Gloria said she stayed at the shooting scene until she saw her son’s body being put into the morgue’s vehicle. Without further explanation, Gloria was told she could see her son’s body at the morgue at 11 a.m. that same day.

But when Gloria arrived at the morgue at the scheduled time, she was told the autopsy report was not yet ready.

“It took them weeks [to complete the report],” Gloria said.

Five years after her son’s death, dressed in jeans, a red leather jacket and black boots, she walked several blocks from her apartment to a place that evoked bitter memories.

Cigarette in hand, Gloria signaled where she found her son’s car. “[When he died], it felt like it [was] the end of the world for [me],” she said.

On her way back to her three-bedroom apartment, Gloria said her family still celebrated Darius’ 11-year-old daughter’s birthday party the day after his death.

“[We wanted] to live up to his spirit,” Gloria Pinex said. “I [was] down, but it [was] her day. He was very fatherly oriented. [He] was a good daddy and son.”

The shooting

At approximately 9 p.m. on Jan. 6, 2011, officers Raoul Mosqueda and Gildardo Sierra started their shift—their first time working together. Mosqueda was the driver of the Chevy Tahoe and Sierra sat in the passenger’s seat.

At approximately 9:56 p.m., a series of radio transmissions about a police chase was broadcast over police district four, zone 8 radio channel.

The radio transmissions revealed police officers were chasing a black Oldsmobile Aurora with rims and a temporary plate, wanted for “fleeing and eluding.”

“At the way he was driving and the amount of shootings in the area, we are going to assume there is a weapon in that car,” said police officers on zone 8 radio transmissions.

Mosqueda and Sierra were assigned to the seventh district that night, which corresponds to zone 6 radio channel.

At approximately 10 p.m., a recap of zone 8 radio calls aired over zone 6 channel. The call did not disclose details such as the car’s color or if it had rims and instead described the chase as a “traffic pursuit” rather than as “fleeing and eluding.” The call did not report speculation about a weapon in the car connected to the shootings in the area.

Mosqueda and Sierra may have heard this recap because the call was broadcast over their district’s radio zone, according to the 72-page court decision.

A little after 1:35 a.m. on Jan. 7, both officers encountered a “dark-colored” Oldsmobile Aurora with “temporary plates,” according to Mosqueda’s deposition. Mosqueda claimed he thought this was the vehicle mentioned in the previous call.

According to Mosqueda’s Independent Police Review Authority statement, both officers pulled the car over for that reason alone.

As the judge wrote in his detailed decision, “Mosqueda and Sierra did not do certain things that one might expect police officers pulling over a dangerous vehicle to do.”

First, Mosqueda and Sierra did not call for backup. Secondly, they did not call in to report they were stopping the vehicle and finally, they did not call in the license plate to verify that the Aurora’s plate matched the Aurora from the previous call. If they had done this, they would have found that the license plates were not the same. After pulling over the Aurora, which Darius Pinex was driving, Sierra and Mosqueda got out of their Tahoe and approached the vehicle. Inside the car was also passenger Matthew Colyer, who was sitting in the front passenger’s seat.

The sequence of events that followed was disputed by both sides during the trial. According to court documents, Sierra approached Darius on the driver’s side of the car while Mosqueda approached Colyer from the other side. At some point, Darius reversed the car, hitting a light post. Colyer fell out of the car when the car began to reverse and Mosqueda fell to the ground. Simultaneously, Sierra fired one shot at the car but did not hit the passengers. Darius then drove away from the light post. Mosqueda opened fire and killed Darius.

The first trial: inconsistent versions

In 2012, Gloria filed a second lawsuit against officers Sierra and Mosqueda as well as the City of Chicago. Her first lawsuit had been dismissed with permission to refile a few months before. Because Colyer’s family also filed a previous lawsuit, both families’ lawsuits were consolidated; the lawsuit alleged excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

Attorneys Jordan Marsh, Tom Aumann and Dana Pesha represented Sierra, Mosqueda and the city during the trial.

According to court records, officers Mosqueda and Sierra said they stopped Darius’ car because they believed it matched the description of an Aurora that officers could not pull over hours earlier that night.

Officer Mosqueda claimed he heard the car’s description over his police-car radio from a dispatcher in the Office of Emergency Management and Communications, but not directly from the fourth district calls.

Mosqueda said the dispatcher summarized the fourth district’s car description and said the Aurora was wanted for a shooting or that there might be a gun in the car.

Officer Sierra’s version remained inconsistent. In Sierra’s Independent Police Review Authority statement, he said he heard the same dispatch as Mosqueda, and in his deposition, Sierra claimed he only remembers Mosqueda telling him about it.

According to the officers, when stopped, Darius attempted to drive away, putting Mosqueda and Sierra’s life at risk. Mosqueda said he was pushed down by the car’s open door, and Sierra said he was eventually endangered when Darius sped toward him. That is when the officers opened fire and killed him.

Darius’ and Matthew Colyer’s lawyers claimed the officers aggressively stopped Pinex’s car, rushed out with guns drawn and pointed at them while screaming. Their version also stated that because the officers fired the first shot without reason, Darius attempted to flee.

Mosqueda said he had his gun drawn when exiting the police car because of the dispatcher’s warning that the Aurora was wanted in a shooting or might have had a gun inside.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys asked for a recording of what Mosqueda claimed to have heard on the radio and any other documents related to the recording during the discovery phase of 2012 and 2013 but never received it.

The plaintiffs argued that Mosqueda was lying and that the officers “executed an overly aggressive traffic stop for their own reasons or no reason at all.”

However, on the fourth day of the trial, the city revealed the recording did not mention that the Aurora contained a gun or that the car was wanted for a shooting.

The plaintiffs asked for a directed verdict in their favor or a new trial including attorneys’ fees and costs.

The jury ultimately ruled in favor of Mosqueda and Sierra, but the Court authorized a post-trial discovery phase to determine the extent of the discovery violation.

During the post-trial discovery phase, it became clear to Judge Chang that senior city lawyer Jordan Marsh knew about the OEMC recording and intentionally failed to disclose it.

But Marsh was not the only one who did not provide evidence. Thomas Aumann, the other city lawyer, failed to properly search for the recording and related documents requested by the plaintiffs, Judge Chang found.

Considering these violations, the Court denied a directed verdict but granted a new trial because the first one was unfair to the plaintiffs’ presentation of their case and “was hurt beyond repair by the [undisclosed recording] surprise.”

The Court also awarded plaintiffs attorneys’ fees and costs for the first trial and the post-trial discovery and briefing. Gloria returns to trial on July 18.

Tracy Siska, executive director of the Chicago Justice Project, said organizations such as the Independent Police Review Authority and the Bureau of Internal Affairs are not held accountable for their work because they lack transparency.

“It is very hard to hold anything accountable where there is no transparency,” Siska said.

Siska also said the officers’ use of force should be looked at on a case- by-case basis, but that the police should focus on de-escalation tactics.

“The police in America are quick to use force against any resistance when that clearly is not the best tactic,” Siska said.

However, Siska said he does not think there is anything the police department can do to make police accountability a core CPD value.

“We need political reform, economic development in the community and independence of the police,” Siska added.

Loyola’s Donner said there have been incremental adjustments to change policing and improve police accountability and transparency; however, more needs to be done.

“Misconduct has always been a problem; [excessive] use of force has always been a problem, and it is going to continue to be a problem,” Donner said. “Better hiring, training, policy, supervision [and] transparency can push policing forward, but those things take time, effort and resources. You are not going to see policing change overnight.”

Heading back to court

“The word is there is no word,” said Steve Greenberg, one of Gloria’s attorneys, as he stood outside of the April 19 court hearing room where Gloria and her team of attorneys were offered an undisclosed amount to settle.

Wearing a white shirt, skirt and matching stockings, Gloria sat beside her mother, Gloria Johnson, and gave her family soft smiles.

“I denied the offer,” Gloria told The Chronicle that afternoon. “I did not want that.”

Gloria said she arrived at the hearing open to negotiation, but she was not satisfied with the offer.

“I am looking for my grand-babies to be taken care of,” she said. “I cannot let this slide.”

Gloria is determined to come out victorious this summer.

“I [sought] out the truth, and I got the truth,” she said. “They lied on my son 100 percent, and I am glad I have got the truth…He [is] gone for nothing. He should still be here.”