City youth caught in the crossfire, bear scars of gun violence

Information Courtesy of Chicago Tribune

February 27, 2017

A lack of counseling for children who have experienced trauma can cause them to become “numb to their emotions,” said Waldo Johnson, a professor in the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago.

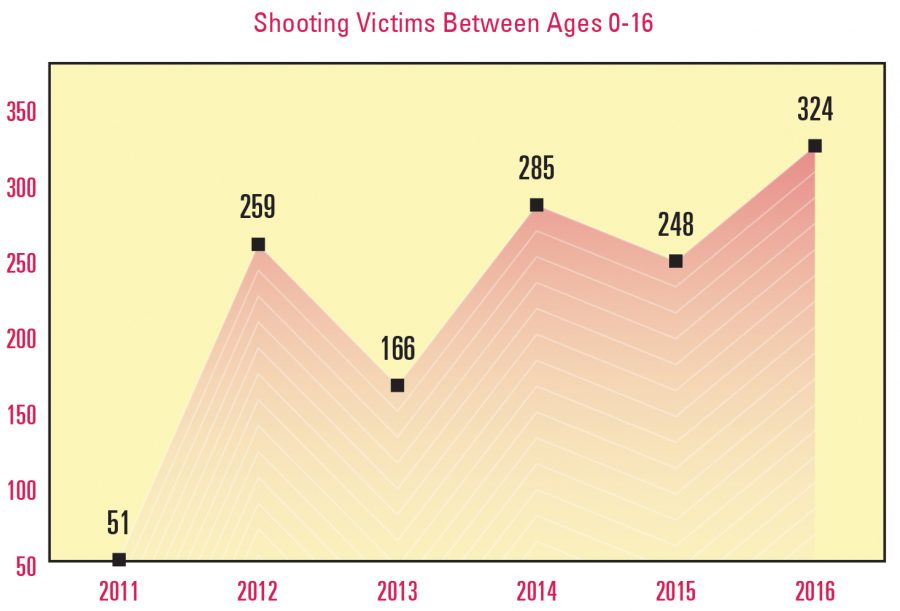

This February has seen a rise in crime in South and West side communities, including the deaths of multiple children—the youngest being a 2-year-old—as homicide statistics continue to rise in the city, following a year that experienced 762 murders.

With seven homicides, Feb. 22 became the deadliest day of 2017, prompting experts to agree that more needs to be done to head the trauma of city youth.

“You can’t arrest homelessness away,” said Dexter Voisin, another professor in the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago. “You can’t arrest lack of opportunity away. Policing is not going to solve this problem by itself.”

According to Voisin, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention—the federal agency responsible for public health—predicted that every homicide in Chicago affects 120 community members. The effects include post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety in the friends and family of those killed.

Voisin said damage is seen in children who witness a homicide or know the victims, and is directly linked to low school attendance records, unsatisfactory school performance and high dropout rates. Dropping out increases the juvenile’s likelihood of becoming involved in organized crime, he added.

“Often, school counselors will be rushed in, and help will be given to those kids,” Voisin said. “The reality is when you have schools with homicide [victims] or murders in communities, those kids have been experiencing ongoing violence often on a daily basis.”

Constant exposure to violence could cause youth to worry about their own safety, Johnson said, and cause them to acquire a weapon. The most recent community violence instances have dealt with juveniles as the ones pulling the trigger, he added.

“We have to think of those individuals as being lost,” Johnson said. “To be engaged in this kind of behavior certainly suggests that something, with respect to their own lives, have gone awry.”

Johnson and others are concerned about the nearly two-year state budget impasse, which has created funding problems for child services in schools and hospitals that address emotional behavior following a traumatic experience.

“The programs and the services designed to address these very concerns are either at great risk of being reduced or of closing down in the communities where they are needed most,” Johnson said.

Andy Wheeler, a support coordinator at John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital, 1969 Ogden Ave., said he works with a program called Healing Hurt People Chicago.

The program pairs children with a trauma intervention specialist, who builds a relationship with them and encourages them to open up. Specialists follow up with their patients for six months to a year after a trauma incident, to assure they are feeling safe in their school, according to Wheeler.

“Right now, we have such a large caseload and such a long waiting list that we have to prioritize those who have been direct victims of community violence,” Wheeler said. “Anybody dealing with community violence could always use more resources.”

Mayor Rahm Emanuel is currently directing more funds toward after-school and youth-mentor programs, such as Becoming a Man and Working on Womanhood, both mentoring programs for youth in at-risk neighborhoods, as reported on Sept. 26, 2016 by The Chronicle

Voisin said city officials should be looking at long-term investments similar to what New York City and Washington D.C. did to combat youth violence and homicides—specifically investing in jobs for youth, as well as mentorship programs.

“You can’t tell a kid, ‘Don’t join a gang,’ if you don’t give them an alternative, viable opportunity,” Voisin said.