Understanding the ‘witch hunt’ in online movements

January 21, 2018

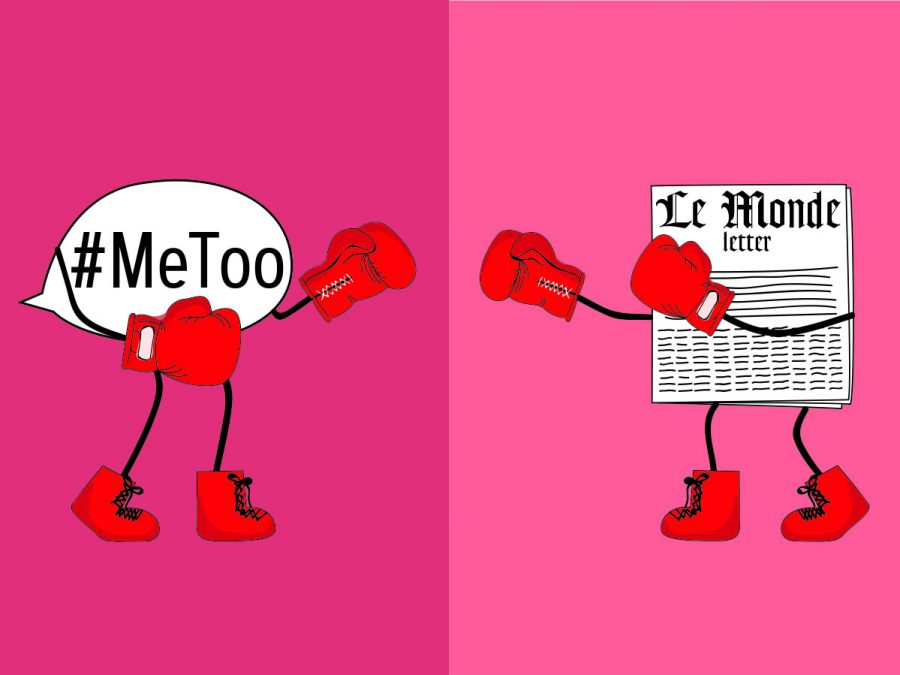

In an open letter published Jan. 9 in the French publication Le Monde, a group of 100 women, including actress Catherine Deneuve, took issue with the Me Too movement, framing it as a “witch hunt.” This letter is emblematic of a continuing conflict between generations of feminists.

The women’s letter did not condemn all of Me Too but said the movement had gone too far, claiming it impinges on women’s freedom to say no and men who are accused of misconduct are expected to resign with no right of due process.

The response to the letter was predictable. Asia Argento, one of the first to speak out about Harvey Weinstein, said on Twitter that the letter tells the world “…how their interiorized misogyny has lobotomized them to the point of no return.” Blows came from all sides, be it from French feminists or Van Badham of The Guardian, who refuted the letter’s accusations of “witch hunts.”

A witch hunt denotes authority bearing down on the voiceless, but with Me Too, it’s quite the opposite: It’s propelled by women rising up against systems and structures that have historically limited their agency.

The letter’s accusations are common against Me Too, Black Lives Matter and similar online-supported movements. They are built on the backs of victims, either people abused by those in powerful positions or black victims of police violence. Their collective pain is charged by a self-righteous public, lacking any figureheads to denounce. It is a new kind of movement with new challenges.

The decentralized nature of the Me Too movement leaves its intent up to interpretation, as there is no manifesto or oligarchy of quotable faces to confront.

The Le Monde letter envisions the Me Too movement as a group of exterminators that deliver “expeditious justice” to what the letter would identify as minor offenses that women are strong enough to handle. Men like Kevin Spacey, Charlie Rose or Matt Lauer had avoided the consequences of their actions for years until victims came forward and investigations were conducted.

To the extent that the “witch hunt” does exist, it’s seen in a recent poll by Ipsos and NPR,where nearly 90 percent of respondents support a zero-tolerance sexual harassment policy. These people likely lost faith in the court system the day Brock Turner was convicted of raping a woman in an alley and only received six months in jail as punishment.

Perhaps it’s the unilateral execution, not the hunt, that those behind the letter are worried about. The letter sees a public indulgent in the catharsis of vigilantism, seeing as no legal justice is ever carried out. Their aggression comes because industries protect their talent and women are bought off for silence.

The Me Too movement acts as a shelter of acceptance and understanding with a focus on truth rather than justice. Victims come forward to relieve, or try to relieve, years of trauma that they felt too belittled or intimidated to divulge.

One can see the letter writers’ reservations, knowing the public’s thirst for justice, but the victims of their ire are hard to feel sorry for. One should be glad for their criticism, as it reminds us to be nuanced in our activism.