White Supremacy 101: oppression in classrooms

October 2, 2017

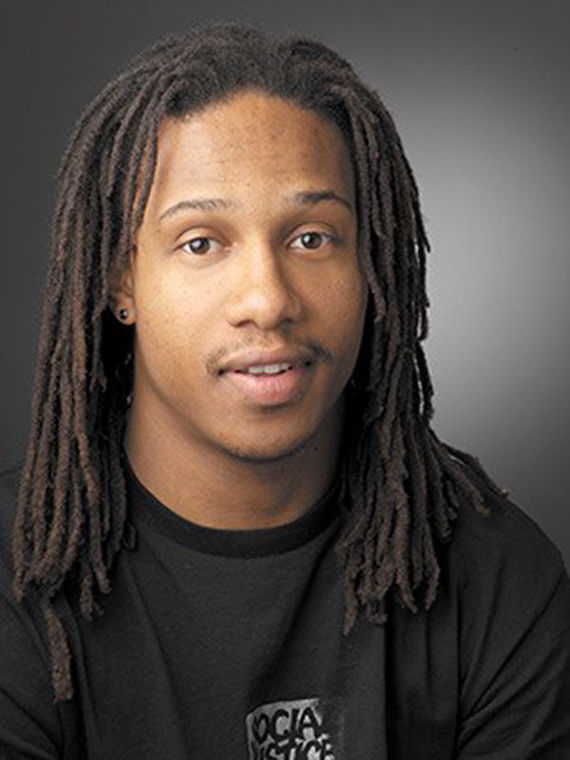

Columbia College Chicago Assembly will be hosting a discussion with David Stovall (pictured) focusing on white supremacy in the classroom.

White supremacy is still prevalent in American classrooms, said David Stovall, an education policy studies and African-American studies professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Acknowledging this concern, Columbia College Chicago Assembly will be hosting “Charlottesville is Everyday: Understanding the Overt and Subtle Legacies of White Supremacy in the Classroom.” The discussion will take place Oct. 2 at Stage Two, 618 S. Michigan Ave., featuring Stovall and Matthew Shenoda, dean of Academic Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

“It’s everything from the curriculum, the design of school space and discipline policies; it’s in our pedagogical practice,” Stovall said.

According to a report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, 109 public schools are named after Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and other prominent Confederates, 27 of these schools being in predominantly black areas. Although a majority of these schools are in former Confederate states, there are signs of white supremacy in schools around the country.

Stovall and Shenoda debated topics for the discussion, but after the rallies and protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, they concluded that white supremacy needed to be the focus.

Stovall said white supremacy should be discussed in classes to understand it as structural ideology, not as individual terror or bigoted events. He cited Christopher Columbus lessons as an example of white supremacy in curriculum.

“This is always a problem in terms of looking at how we understand and shape our historical events,” Stovall said, noting the lack of critical perspective on the story of Columbus and his search for gold that ended in shooting and killing indigenous people.

Oscar Valdez—Columbia alumnus and academic scheduling coordinator in the Humanities, History and Social Science Department —helped organize the panel and said he felt marginalized as a freshman at Columbia when his professor argued that his Latino-themed project would not be successful because everyone does not speak Spanish like him.

Valdez said equitable education—giving students what they need instead of treating everyone the same—is important because it allows different voices to be heard.

ProPublica’s Documenting Hate project has collected accounts of hate speech at more than 120 college campuses nationally since November 2016.

Eritrea Haile, music major and president of the Pan African Student Organization, said she went to a predominantly black school from kindergarten to sixth grade before transferring to a predominantly white Jewish school, where she was the only black student in her class.

Haile said she would not have felt alienated in school if there was more equitable education regarding white supremacy and race.

If you are sharing a space, it’s important to understand one another, Haile said.

A study from the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that two-thirds of hate crimes go unreported to the police, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. The same study shows that out of 867 post-election hate incidents, 183 occurred in K–12 institutions and 140 were on college campuses across the country.

Stovall says people refrain from addressing white supremacy because engagement is perceived as divisive.

“It’s about dedication to recognizing how white supremacy operates,” Stovall said. “We have to engage and be uncomfortable. We have to be able to rest in our discomfort.”