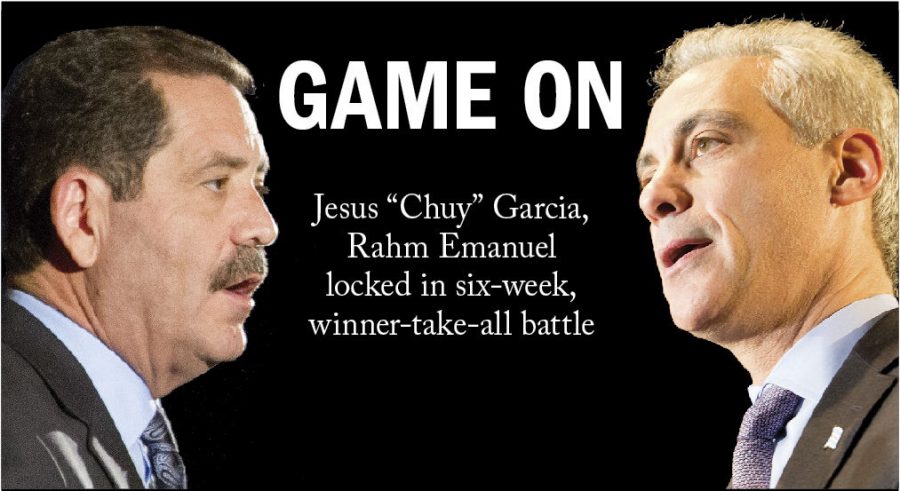

Emanuel, Garcia thrust into April runoff

Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Jesus “Chuy” Garcia are being catapulted into six more weeks of campaigning after the Feb. 24 election resulted in a runoff set for April 7, the first since the city switched from the partisan primary system in 1995. Emanuel earned 45.4 percent of the vote and Garcia earned 33.9 percent. Both candidates face harrowing challenges. Garcia must establish himself as more than “the neighborhood guy,” but as a leader who can run a city plagued by chronic problems. Emanuel fights against a record marked with school closings, teacher strikes and city violence.

March 2, 2015

Mayor Rahm Emanuel is ready for round two against Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, a Cook County commissioner, after failing to get a majority of the votes needed for a Feb. 24 reelection.

The two are now propelled into a charged runoff race. With all precincts reporting, Emanuel received 45.4 percent of the vote, while Garcia lagged behind with 33.9 percent. The two will campaign for the next six weeks, and Chicago voters will decide the winner April 7.

The Feb. 24 turnout tied Chicago’s historic low of 33 percent for the 2007 mayoral election—Richard M. Daley’s final term.

Against Chicagoans’ expectations, Emanuel could not convert his huge war chest and onslaught of political ads into mayoralty.

Emanuel strutted onstage at Chicago Journeymen Plumbers Union Hall, 1340 W. Washington Blvd., on the evening of Feb. 24 with a triumphant look nonetheless and said, “We have come a long way and have a little bit further to go.”

As the crowd chanted “We want Rahm,” Emanuel pointed over their heads and said, “I want you.”

Rahm told his supporters to enjoy the night, promising that “tomorrow morning, I’ll see you out at the el stops.”

Garcia and Emanuel can expect to face disparate challenges in coming weeks. Emanuel’s name carries a stigma in some quarters while Garcia, despite his long public service career as an alderman, state senator and Cook County commissioner, is not yet a household name for many Chicagoans.

Laura Washington, a political analyst for ABC-7, Chicago Sun-Times columnist and a Winter 2015 fellow at the University of Chicago’s Institute of Politics, said even if Chicagoans do know Garcia’s name, they do not really know what he stands for.

“That raises the question, ‘Where have you been all these years?’” she said. “If you’ve been around since the days of [Mayor] Harold Washington and you’ve had all these political positions and offices, why haven’t I heard anything about you? His job is both to educate folks about who he is, but also to build a personal relationship and a trust with voters that, ‘I’m a guy that you’re just getting to know but that you can trust.’ That’s a lot to do in six weeks.”

Garcia labeled himself the “neighborhood guy” during mayoral debates but articulated few solutions to solve chronic metropolitan problems such as policing and education.

“He’s going to have to put some meat on the bones of his ideas for turning the city around,” Washington said. “His proposal of adding 1,000 police is a classic example. He’s been asked repeatedly, ‘How are you going to pay for that?’ and he’s talked about saving money through cutting overtime, but the experts say that won’t even get close.”

Emanuel has been seen as a political import from Washington with a short fuse and an attitude problem. Many have criticized “rubberstamping”—approving decisions without sufficient analysis—by the City Council, which to some voters seems to be in lockstep with the mayor and his policies.

Dick Simpson, political science professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and former alderman, said Emanuel is no longer invincible. Simpson said the elections are a referendum on both the mayor and City Council, as evidenced by the 19 aldermanic runoff elections threatening to unseat some of Emanuel’s loyal supporters.

“Rahm’s arrogance, or his inability to involve people in either deciding what to do or being part of doing it after a decision is made [could be an issue],” Simpson said.

Emanuel’s move to close 49 Chicago public schools in 2013 attracted vocal criticism from angry parents and teachers. The year before, the Chicago Teachers Union had its first strike in 25 years and Emanuel handled the negotiations with his now signature vitriol, refusing to meet with CTU President Karen Lewis on several occasions.

Lewis dropped out of the race and endorsed Garcia after being diagnosed with a brain tumor in October.

“The mayor’s decision to close 50 schools and drive teachers out on strike for the first time in 25 years was the defining moment for his administration,” Garcia said at his election party. “Mayor Emanuel likes to say he makes hard choices, but there is a difference between making hard choices and being hardheaded.”

In a city troubled by racism and segregation, both campaigns have made haste on securing black votes. Emanuel and Garcia both tried Feb. 25 to gain the endorsement of Willie Wilson, the black entrepreneur against whom they had run. Wilson received 10 percent of the vote.

After conceding, Wilson said, “We’ve made a difference in the City of Chicago.”

Washington said the black vote is a significant portion of the electorate and that Chicago’s black population is highly dissatisfied with the status quo.

“Whoever can appeal to that vote is going to be in a real good position,” she said.

Jim Allen, a spokesman for Chicago Board of Election Commissioners, said the turnout is expected to be higher in the runoff election. The board has already received far more inquiries about April’s election than it did about the first election, he said.

“I think it’s safe to say it’s higher,” Allen said. “Normally it’s lower in a runoff election, but here, in addition to the aldermanic runoff, you’re looking at a mayoral runoff, and that just hasn’t happened. This will be new ground for the Chicago electorate.”