New treatment gives second chance to leukemia patients at U of Chicago

September 11, 2017

The University of Chicago Medical Center is one of the first hospitals to offer a new cancer treatment that is giving late-stage leukemia and lymphoma patients another chance for remission.

A pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment CAR T-Cell therapy, called Kymriah, has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration Aug. 30. It was developed by the University of Pennsylvania and distributed by Novartis, a Switzerland-based pharmaceutical company.

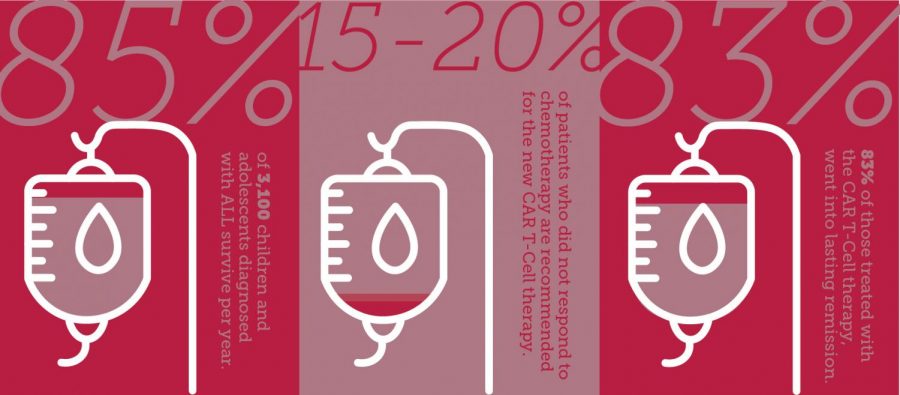

According to the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, acute lymphoblastic leukemia is the most common cancer in children, with more than 3,100 children and adolescents diagnosed annually. For 15 to 20 percent of children whose disease does not respond to chemotherapy, the average life expectancy is six months, said Dr. Michael Bishop, a medical professor and director of cellular therapy program at U of C.

CAR T-cells is a novel form of immunotherapy, Bishop said , that extracts a patient’s own immune cells, called B- and T-lymphocytes, from a blood sample and then modifies them with a virus that targets and kills leukemia cells. The cells are then injected into the patient’s blood, where they attach to CD19 leukemia proteins.

“When it targets the protein and attacks it, it actually turns on the T-lymphocytes,” Bishop said. “It then becomes activated, starts doubling and it actually kills the leukemia cells.

According to U of C, 83 percent of the patients in the clinical trial responded to the treatment. While Kymriah has been approved for pediatric leukemia, tests are still underway for adults. Bishop said doctors are seeing similar, positive results in adults from the clinical trials as they did in children.

“It is anticipated that within less than six months, you’re going to see an approval of this type of therapy for adult lymphoma,” Bishop said.

Scott McIntyre, 53, from South Bend, Indiana, was the first patient at U of C to participate in the clinical trial. McIntyre was diagnosed with Stage 3 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in 2013. After R-ICE chemo, stem cell and various clinical trials from 2014 to 2016, McIntyre was the perfect candidate for the CAR T-cell therapy.

He was unaware he had previously only been given six months to live when he started the process in May 2016.

“The whole team really believed in this treatment,” he said. “They saw great responses so far, and it was a possibility of treating someone who had a zero percent chance of surviving.”

McIntyre is now 16 months into remission, and said he is back to work, his strength and stamina have returned, and he can once again play 18 holes at the golf course.

“They told me, ‘No matter what the outcome, what you’re doing is setting the bar and helping people down the road,’” McIntyre said.

The therapy is not without side effects, which can include flu-like symptoms such as high fevers and sudden blood pressure drops, as well as neurotoxicity, leading to confusion and seizures.

“When [T-cells] are turned on, it can get so severe that about half of the patients end up in the intensive care unit for close monitoring,” Bishop said. “We are able to manage that in more than 95 percent of patients, but there have been cases that adults died from the complications.”

Bishop said no patients have died from the therapy at U of C.

Organizations including the Campaign for Sustainable Rx Pricing have criticized the high cost of the treatment. Novartis announced Kymriah would cost about $475,000, a steep price compared to other cancer treatments, said John Rother, CEO and president of the National Coalition on Healthcare and executive director of the Campaign for Sustainable Rx Drug.

“With the new class of drugs, we are seeing prices going through the roof that don’t seem to have any relationship to the cost of development, production or the savings that might be achieved as a result of their use,” Rother said.

For 20 years, scientists and doctors have researched CAR T-cell therapy with federal, nonprofit and pharmaceutical funding. While some like Rother argue the commercial price is not justified, Bishop said that without pharmaceutical companies making an investment, the research would not be possible.

“Hundreds of millions of dollars went into trying to develop this product,” Bishop said. “There are large investments from pharmaceuticals to make factories that can mass produce this to the quality that is necessary to ensure that every patient is getting a quality product.”