Virtual name game sheds light on social norms

Virtual name game sheds light on social norms

February 16, 2015

After “Twilight,” by Stephanie Meyer, was released in 2008, the name “Isabella” became the most popular name for girls in the United States and “Cullen” as a boy’s name soared upward by 300 ranks, according to data released by the U.S. Social Security Administration in 2009.

While the names’ rise in popularity could be attributed to “Twilight’s” success, a study published in the Feb. 2 Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal has found that the emergence of social conventions is not a direct result of popular media.

“We tested whether a consensus emerges without any central authority, and without the individuals knowing that they are in the population or without knowing that they are trying to collectively agree,” said Andrea Baronchelli, a lecturer at City University London and co-author of the study.

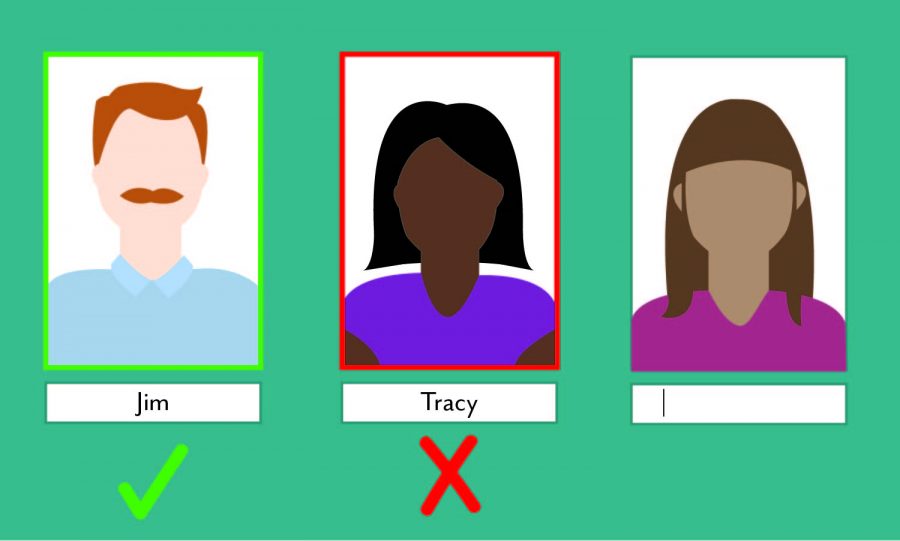

Baronchelli and co-author Damon Centola, an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania designed an online game in which partners were paired and shown a picture of a face and instructed to give the face a name. If both partners submitted the same name, they were rewarded with either 25 or 50 cents. For each incompatible name submission, each individual lost 25 cents. The researchers created three “networks” for participants to unknowingly participate in—a geographical network with their four closest neighbors; a “small world network,” with the same set of random partners from the geographical network and a random network that changed partners each round.

“What you want to do is get the name that your partner will type,” Baronchelli said. “The thing that you don’t know as a user is that you are the node of a social network. The partners you are playing with are actually your neighbors in the social network and your social circle that is defined by us as experimenters. What we want to observe is whether the whole population will reach an agreement or not.”

The researchers were surprised to observe consistent patterns in both geographically linked and small world networks.

“For the first five to 10 rounds [of the game,] it’s just a huge mess,” Baronchelli said. “Many names compete and there’s no order. People get frustrated and there’s no consensus. And then, at a certain point, one of these names started to be amplified and then the whole population was using it. That was great because we know a consensus can emerge without a central authority of people knowing they are trying to agree.”

The structure of the social network affected how quickly the groups could come to a consensus, according to Baronchelli.

“In particular, when the social network is very connected, we do observe an agreement,” Baronchelli said. “When we have a spatial network, in which you just play with your spatial neighbors, what happens is that different regions of the network develop a consensus on different norms. You will have a region that agrees that the name [of the face pictured] is Sandra, you will have a region that says the name is Joanna and a region that agrees that the name is Alexis.”

The study expands upon prior theories about the emergence of social norms, according to Robb Willer, an associate professor of sociology at Stanford University.

“One way that social norms form is through the emergence of patterns of regular behavior that then become viewed with a sense of oughtness,” Willer said. “If everybody is doing something, whatever that thing may be, there is reason to believe that people start to think that that convention is also something that ought to be done.”

The study could also provide insight into how certain vocabulary words become popular. According to Baronchelli, the term “spam” in reference to junk email is a shining example of how vocabulary can emerge abnormally and arise as a commonly used term.

“‘Spam’ was initially used for junk email as a joke because there is a very interesting famous Monty Python sketch in which they say ‘spam’ a lot,” Baronchelli said. “Without any central authority, we now agree that’s the name we use to indicate an email we don’t want to receive. In the beginning, there were competing names, like ‘junk email,’ but now, basically, everyone calls it ‘spam.’”

According to an emailed statement from Adrienne Keller, the research director at the National Social Norms Institute, the study’s findings provide notable insight into how social norms emerge.

“This is fascinating research,” Keller said in the email. “I suspect that the formation of social norms may be comparable to the [cause] of chronic diseases. Many paths, different mixes of paths, can lead to the same outcome. Nonetheless, the article certainly stimulates thinking and questions.”

Future research will explore how social norms can be controlled and possibly improve the public’s understanding of science-related issues such as global warming and vaccinations that are commonly debated, according to Baronchelli.

“Our next big question is, is it possible to move a group from a consensus on a given norm to a consensus on a different norm?” Baronchelli said. “We have more insight now on how the dynamics of consensus works so the next big question is, can we somehow understand why social conventions change and can we, in a sense, help the movement from a bad convention to a good convention?”