City funds local health while sparking debate

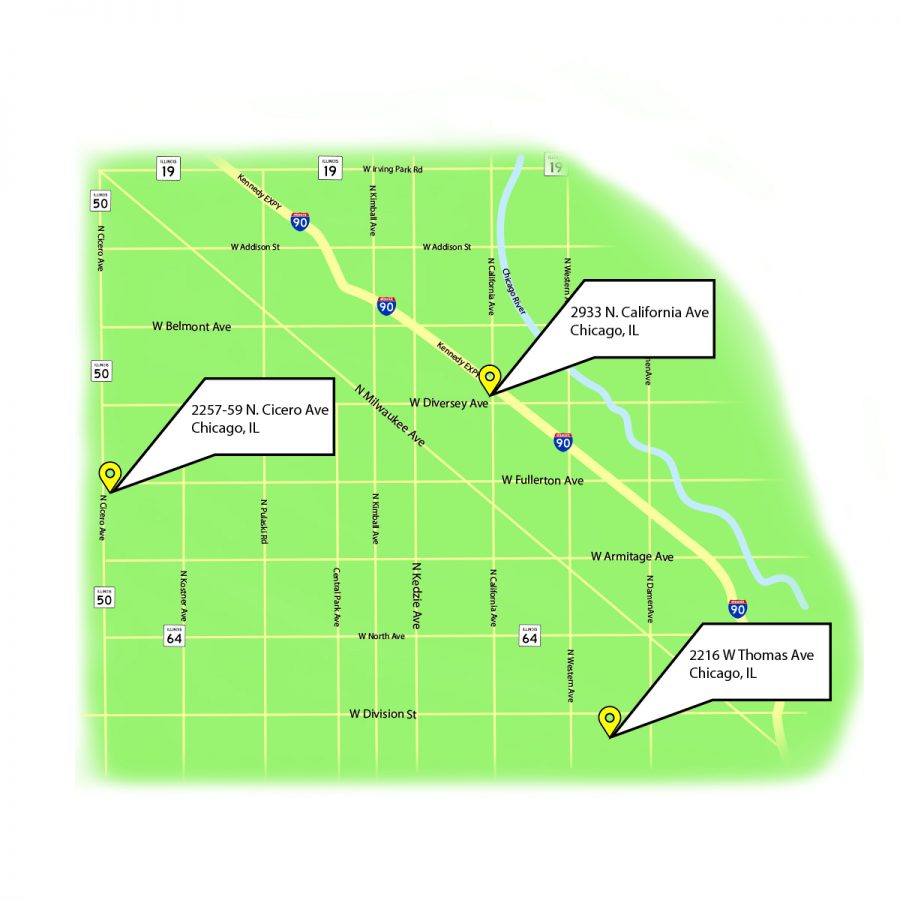

9000 S. Stony Island Ave. Location is south of map

January 28, 2018

Chicago has plans to provide accessible health care to more underserved residents, but the new plan comes with baggage, according to experts.

City Council approved $5.55 million in Tax Increment Financing funds for Presence Health, which operates clinics and hospitals in the Chicago area, to update four neighborhood medical facilities in underserved communities.

The four local locations are Calumet Heights, 9000 S. Stony Island Ave.; Avondale, 2933 N. California Ave.; Belmont Cragin, 2257-59 N. Cicero Ave.; and West Town, 2216 W. Thomas Ave. When completed, these facilities will care for an estimated 22,500 people as well as create 39 permanent jobs. In addition to updates at the four locations, Presence Health also expanded its headquarters, 200 S. Wacker Drive, according to a Jan. 17 mayoral press release.

Each medical facility will serve a different purpose to reflect its respective community’s needs, such as primary care at Belmont Cragin and state-of-the-art cancer care at West Town, according to the press release.

“[The grant money] underscores the committed partnership of Presence Health and Chicago in seeing that minority communities on the West Side as well as medical homes in distressed neighborhoods where once there was a care void, now receive compassionate, accessible [and] high quality care,” said Michael Englehart, president and CEO of Presence Health in a Jan. 23 email statement to The Chronicle.

Multiple factors create healthcare deserts, according Craig Klugman, a professor in the Department of Health Sciences at DePaul University.

Hospitals are expensive to operate, Klugman said, and a small independent hospital will not have the resources to serve communities that have greater needs.

Presence Health has sufficient resources to draw from to allow these neighborhood locations to stay afloat, he noted.

“It’s nice that there is a company willing to step forth and help provide services for communities that been underserved in the past,” Klugman said.

Another contributor to health-care deserts is a belief that smaller community hospitals may not be as good as large teaching hospitals. This attitude can deprive small hospitals of resources, according to Klugman.

While the expansion of four clinics increases those neighborhoods’ health-care accessibility, some critics think funding should have gone to a provider that offers comprehensive women’s reproductive care instead of Presence Health, which is a chain of Catholic hospitals and medical facilities.

“[It’s] outrageous that city money is support[ing] institutions that don’t provide a full range of health services,” said Margie Schaps, executive director of the Health and Policy Research Group.

While Presence Health may not offer birth control products or perform abortions, there are other providers in the city serving that need, said Robert Gilligan, executive director of the Catholic Conference of Illinois.

“[The people in these neighborhoods] need screenings for hypertension, they need screenings for cancer [and] they need urgent care,” Gilligan said. “That is what Catholic health care is delivering.”

Klugman said there are other options to expand female reproductive rights in these communities while Presence Health still gets financial assistance.

“Other cities where the Catholic hospital system has bought all the hospitals out, they have formed semi-independent clinics [for comprehensive women’s care],” Klugman said. “That way they can maintain their faith identity but also serve the needs of the women of the community.”