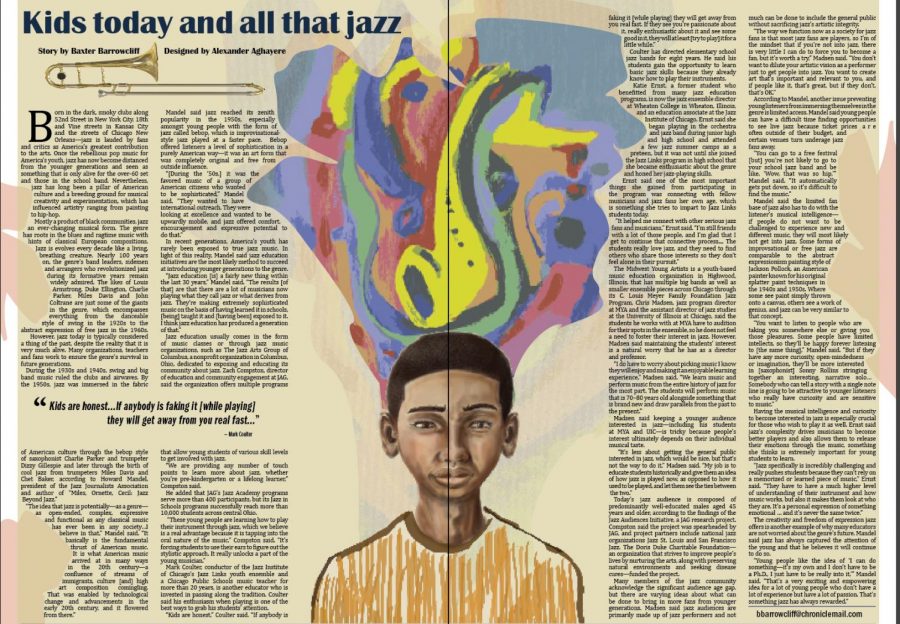

Kids today and all that jazz

Kids today and all that jazz

March 16, 2015

Born in the dark, smoky clubs along 52nd Street in New York City, 18th and Vine streets in Kansas City and the streets of Chicago and New Orleans—jazz is lauded by fans and critics as America’s greatest contribution to the arts. Once the rebellious pop music for America’s youth, jazz has now become distanced from the younger generations and seen as something that is only alive for the over-60 set and those in the school band. Nevertheless, jazz has long been a pillar of American culture and a breeding ground for musical creativity and experimentation, which has influenced artistry ranging from painting to hip-hop.

Mostly a product of black communities, jazz is an ever-changing musical form. The genre has roots in the blues and ragtime music with hints of classical European compositions. Jazz evolves every decade like a living, breathing creature. Nearly 100 years on, the genre’s band leaders, sidemen and arrangers who revolutionized jazz during its formative years remain widely admired. The likes of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and John Coltrane are just some of the giants in the genre, which encompasses everything from the danceable style of swing in the 1920s to the abstract expression of free jazz in the 1960s.

However, jazz today is typically considered a thing of the past, despite the reality that it is very much alive. Many organizations, teachers and fans work to ensure the genre’s survival in future generations.

During the 1930s and 1940s, swing and big band music ruled the clubs and airwaves. By the 1950s, jazz was immersed in the fabric of American culture through the bebop style of saxophonist Charlie Parker and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and later through the birth of cool jazz from trumpeters Miles Davis and Chet Baker, according to Howard Mandel, president of the Jazz Journalists Association and author of “Miles, Ornette, Cecil: Jazz Beyond Jazz.”

“The idea that jazz is potentially—as a genre—as open-ended, complex, expressive and functional as any classical music has ever been in any society…I believe in that,” Mandel said. “It basically is the fundamental thrust of American music. It is what American music arrived at in many ways in the 20th century—a confluence of streams of immigrants, culture [and] high art composition comingling. That was enabled by technological change and advancements in the early 20th century, and it flowered from there.”

Mandel said jazz reached its zenith popularity in the 1950s, especially amongst young people with the form of jazz called bebop, which is improvisational-style jazz played at a faster pace. Bebop offered listeners a level of sophistication in a purely American way—it was an art form that was completely original and free from outside influence.

“[During the ‘50s,] it was the favored music of a group of American citizens who wanted to be sophisticated,” Mandel said. “They wanted to have international outreach. They were looking at excellence and wanted to be upwardly mobile, and jazz offered comfort, encouragement and expressive potential to do that.”

In recent generations, America’s youth has rarely been exposed to true jazz music. In light of this reality, Mandel said jazz education initiatives are the most likely method to succeed at introducing younger generations to the genre.

“Jazz education [is] a fairly new thing within the last 30 years,” Mandel said. “The results [of that] are that there are a lot of musicians now playing what they call jazz or what derives from jazz. They’re making extremely sophisticated music on the basis of having learned it in schools, [being] taught it and [having been] exposed to it. I think jazz education has produced a generation of that.”

Jazz education usually comes in the form of music classes or through jazz music organizations, such as The Jazz Arts Group of Columbus, a nonprofit organization in Columbus, Ohio, dedicated to exposing and educating its community about jazz. Zach Compston, director of education and community engagement at JAG, said the organization offers multiple programs that allow young students of various skill levels to get involved with jazz.

“We are providing any number of touch points to learn more about jazz, whether you’re pre-kindergarten or a lifelong learner,” Compston said.

He added that JAG’s Jazz Academy programs serve more than 400 participants, but its Jazz in Schools programs successfully reach more than 10,000 students across central Ohio.

“These young people are learning how to play their instrument through jazz, which we believe is a real advantage because it is tapping into the oral nature of the music,” Compston said. “It’s forcing students to use their ears to figure out the stylistic approach. It really unlocks a part of the young musician.”

Mark Coulter, conductor of the Jazz Institute of Chicago’s Jazz Links youth ensemble and a Chicago Public Schools music teacher for more than 20 years, is another educator who is invested in passing along the tradition. Coulter said his enthusiasm when playing is one of the best ways to grab his students’ attention.

“Kids are honest,” Coulter said. “If anybody is faking it [while playing] they will get away from you real fast. If they see you’re passionate about it, really enthusiastic about it and see some good in it, they will at least [try to play] it for a little while.”

Coulter has directed elementary school jazz bands for eight years. He said his students gain the opportunity to learn basic jazz skills because they already know how to play their instruments.

Katie Ernst, a former student who benefitted from many jazz education programs, is now the jazz ensemble director at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, and an education associate at the Jazz Institute of Chicago. Ernst said she began playing in the orchestra and jazz band during junior high and high school and attended a few jazz summer camps as a preteen, but it was not until she joined the Jazz Links program in high school that she became enthusiastic about the genre and honed her jazz-playing skills.

Ernst said one of the most important things she gained from participating in the program was connecting with fellow musicians and jazz fans her own age, which is something she tries to impart to Jazz Links students today.

“It helped me connect with other serious jazz fans and musicians,” Ernst said. “I’m still friends with a lot of those people, and I’m glad that I get to continue that connective process…. The students really love jazz, and they need to find others who share those interests so they don’t feel alone in their pursuit.”

The Midwest Young Artists is a youth-based music education organization in Highwood, Illinois, that has multiple big bands as well as smaller ensemble pieces across Chicago through its C. Louis Meyer Family Foundation Jazz Program. Chris Madsen, jazz program director at MYA and the assistant director of jazz studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said the students he works with at MYA have to audition for their spots in the ensemble, so he does not feel a need to foster their interest in jazz. However, Madsen said maintaining the students’ interest is a natural worry that he has as a director and professor.

“I do have to worry about picking music I know they will enjoy and making it an enjoyable learning experience,” Madsen said. “We learn music and perform music from the entire history of jazz for the most part. The students will perform music that is 70–80 years old alongside something that is brand new and draw parallels from the past to the present.”

Madsen said keeping a younger audience interested in jazz—including his students at MYA and UIC—is tricky because people’s interest ultimately depends on their individual musical taste.

“It’s less about getting the general public interested in jazz, which would be nice, but that’s not the way to do it,” Madsen said. “My job is to educate students historically and give them an idea of how jazz is played now, as opposed to how it used to be played, and let them see the ties between the two.”

Today’s jazz audience is composed of predominantly well-educated males aged 45 years and older, according to the findings of the Jazz Audiences Initiative, a JAG research project. Compston said the project was spearheaded by JAG, and project partners include national jazz organizations Jazz St. Louis and San Francisco Jazz. The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation—an organization that strives to improve people’s lives by nurturing the arts, along with preserving natural environments and seeking disease cures—funded the project.

Many members of the jazz community acknowledge the significant audience age gap, but there are varying ideas about what can be done to bring in more fans from younger generations. Madsen said jazz audiences are primarily made up of jazz performers and not much can be done to include the general public without sacrificing jazz’s artistic integrity.

“The way we function now as a society for jazz fans is that most jazz fans are players, so I’m of the mindset that if you’re not into jazz, there is very little I can do to force you to become a fan, but it’s worth a try,” Madsen said. “You don’t want to dilute your artistic vision as a performer just to get people into jazz. You want to create art that’s important and relevant to you, and if people like it, that’s great, but if they don’t, that’s OK.”

According to Mandel, another issue preventing young listeners from immersing themselves in the genre is limited access. Mandel said young people can have a difficult time finding opportunities to see live jazz because ticket prices are often outside of their budget, and certain venues turn underage jazz fans away.

“You can go to a free festival [but] you’re not likely to go to your school jazz band and be like, ‘Wow, that was so hip,’” Mandel said. “It automatically gets put down, so it’s difficult to find the music.”

Mandel said the limited fan base of jazz also has to do with the listener’s musical intelligence—if people do not want to be challenged to experience new and different music, they will most likely not get into jazz. Some forms of improvsational or free jazz are comparable to the abstract expressionism painting style of Jackson Pollock, an American painter known for his original splatter paint techniques in the 1940s and 1950s. Where some see paint simply thrown onto a canvas, others see a work of genius, and jazz can be very similar to that concept.

“You want to listen to people who are taking you somewhere else or giving you those pleasures. Some people have limited intellects, so they’ll be happy forever listening to [the same thing],” Mandel said. “But if they have any more curiosity, open-mindedness or imagination, they’ll be more interested in [saxophonist] Sonny Rollins stringing together an interesting, narrative solo… Somebody who can tell a story with a single note line is going to be attractive to younger listeners who really have curiosity and are sensitive to music.”

Having the musical intelligence and curiosity to become interested in jazz is especially crucial for those who wish to play it as well. Ernst said jazz’s complexity drives musicians to become better players and also allows them to release their emotions through the music, something she thinks is extremely important for young students to learn.

“Jazz specifically is incredibly challenging and really pushes students because they can’t rely on a memorized or learned piece of music,” Ernst said. “They have to have a much higher level of understanding of their instrument and how music works, but also it makes them look at who they are. It’s a personal expression of something emotional … and it’s never the same twice.”

The creativity and freedom of expression jazz offers is another example of why many educators are not worried about the genre’s future. Mandel said jazz has always captured the attention of the young and that he believes it will continue to do so.

“Young people like the idea of ‘I can do something—it’s my own and I don’t have to be a Ph.D., I just have to be really into it,’” Mandel said. “That’s a very exciting and empowering idea for a lot of young people who don’t have a lot of experience but have a lot of passion. That’s something jazz has always rewarded.”