Speech-mimicking orangutan speaks volumes

Speech-mimicking orangutan speaks volumes

February 2, 2015

Little is known about the evolution of speech from humanity’s distant past. However, one orangutan named Tilda at Germany’s Cologne Zoo has brought researchers closer to an understanding of these unknown vocal origins.

A study published Jan. 8 in the journal PLOS ONE revealed that orangutans are capable of producing vocalizations that mimic the rhythm and speed of human speech.

“We knew that orangutans could learn human sounds,” said Adriano Lameira, lead author of the study. “We did not know, however, that these calls could include so many speech-like features, such as rhythm and consonant-like and vowel-like components. We are indeed getting cumulative data saying [orangutans] may be able to learn much more.”

This finding could answer questions about whether early-evolutionary humans could produce sounds before developing the modern vocal tract. The research team, composed of scientists from Princeton University, Liverpool John Moores University, Indiana University and the Indianapolis Zoo, was originally studying the whistling abilities of apes when they discovered an orangutan producing speech that mimicked human sounds, according to Lameira.

“We produce, on average, five consonants and five vowels per second, and this is exactly what we saw this individual doing,” Lameira said. “She was producing some calls that were acoustically more similar to consonants and some that were acoustically more similar to vowels. This was quite important because when [humans] open our mouths very quickly, we are stringing together vowels and consonants to put up words.”

These speech patterns have never been recorded in other apes. Nava Greenblatt, a lead keeper at the Brookfield Zoo, said orangutans often communicate with her non-verbally, although vocalizations such as squeaks and grunts are not uncommon.

“They do occasionally communicate with vocalizations that we hear,” Greenblatt said. “We understand that those vocalizations are also heard in the wild. One way that they try to get our attention, because they can’t really speak to us, is to blow raspberries. We don’t see them doing that to each other; that seems to be a learned behavior that they do to us to get our attention.”

Researchers are hypothesizing that Tilda’s replication of human speech patterns is also learned behavior, like blowing raspberries or whistling. Tilda has been around humans for most of her 50 years. Before being relocated to the zoo, she was owned by European families and was involved in the entertainment industry. According to Lameria, if the behavior was learned, it could provide new insight into the similarities between humans and apes.

“We are led to conclude that she learned these calls,” Lameira said. “That’s also the case in humans. No one is born knowing how to speak. It’s part of the learning of any child to learn the consonants and vowels of the mother tongue and learn to string those two together.”

The research raises questions about the evolutionary difference between humans and other species, according to Philip Lieberman, a specialist in the evolution of human speech and professor of cognitive and linguistic sciences at Brown University.

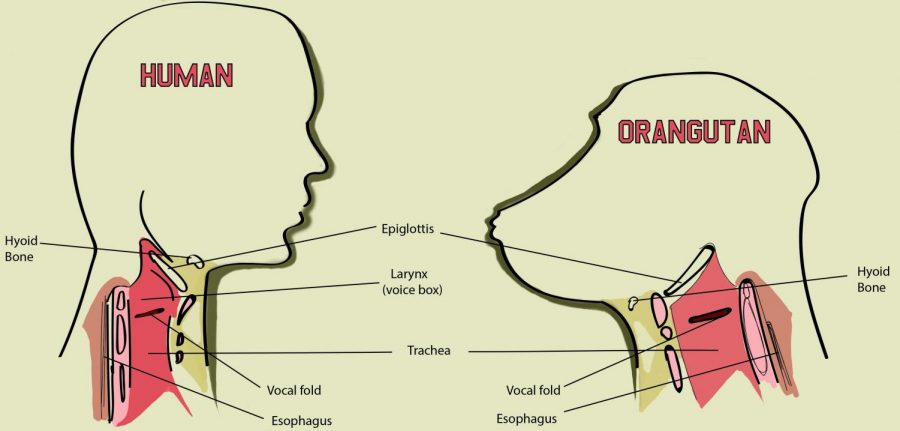

“It’s become apparent that the human brain isn’t fundamentally so different from other species,” Lieberman said. “Human speech goes back a long ways. The larynx is not all that different from a human to a chimpanzee, so you see modifications over the course of time.”

According to Lameira, this study could lead to further research about how young children learn speech as well as other correlations between ape and human evolution.

“It’s important to point out that historically, there is this idea that we cannot learn much about the evolution of speech or language from primates, that we have to go and study birds and whales because they are vocal learners,” Lameira said. “Our study shows that this view is naive and minimalistic. The more we are explore on this path, the more we are going to discover.”