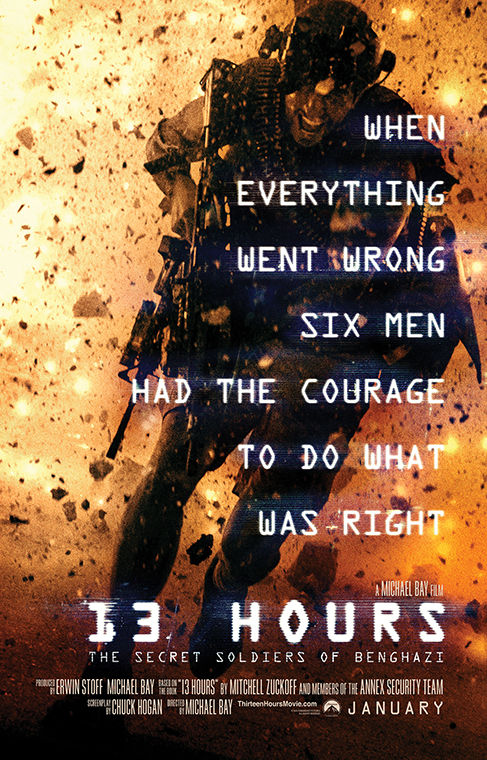

The innocence of Michael Bay: a review of ‘13 Hours’

“13 Hours” depicts the Benghazi attack of 2012.

January 25, 2016

Michael Bay strives to get back to his roots—however flimsy those may be—with “13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi,” a grueling and supposedly true-to-life representation of the 2012 attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, where the U.S. ambassador to Libya, Chris Stevens, was killed.

Tackling his most serious subject matter since 2001’s “Pearl Harbor,” Bay seems painfully aware of the bottom-shelf reputation he holds among critics. In “13 Hours” he tries to rectify his reputation by attempting to repress his infamous tropes for a more subdued, palatable approach to filmmaking.

If Bay was directing a similar project without the same sensitive political baggage, he might have had a fairer chance at making an enjoyable film. But this one was doomed from the start. Of all the talented directors in Hollywood, Bay’s vision is particularly ill-equipped for the intricacies of the Arab Spring aftermath.

If the “Transformers” franchise is any indication, Bay is playing it a little more low-key than he is used to in “13 Hours,” but he is boldly doubling down on his visual brand by making everything visually “popping” and vibrant. The oranges have never been so orange. The blues have never been so blue. The camera is constantly moving, whether there is a massive gunfight or just two folks chatting, and Bay enthusiastically takes advantage of slow-motion, as always.

The score and sound design are tailored to hammer home each emotional cue in the film, combining to make viewers feel like Bay himself has his hand on the back of their heads, forcibly submersing them in blood and bone. However, Bay still manages to shoehorn his immature sense of humor, abject product placement for McDonald’s and an ironic instance of the protagonist telling a woman to shut up and put on her hijab.

The same old “Bayhem” we’ve come to expect isn’t suited to the gravity of the Benghazi attack, and the film is only slightly salvageable by grace of the leading actors’ performances.

As CIA security contractors Jack Silva and Tyrone S. Woods, John Krasinski and James Badge Dale bring just enough nuance to the table to make “13 Hours” tolerable. Though we don’t get a sense of the real people these characters are based on, at least the two leading roles are not empty husks like the rest of the cast.

With the clunky dialogue they have to work with, that is no small feat. Most of the characters, especially the big bad chief, Bob (portrayed by David Costabile), are so bound by Bay’s formulaic grasp that they no longer resemble reality. Bay often resorts to reminding viewers that these people all have families every 10 minutes or so in an effort to get them to care.

As evidenced by the enduring triumphs of escapist sci-fi films “The Martian” and “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” Americans have not exactly been clamoring for a gritty war movie, mongering or not. This begs the question, why was “13 Hours” made? Was it a cash-grab to capitalize on the successes of “American Sniper” and “Fury?” If that was the goal, the film has already failed by splitting its audiences along partisan lines, however inadvertently that may be.

Bay has touted “13 Hours” as politically neutral, even though Paramount has sold the movie toward viewers whose favorite Vietnam movie is John Wayne’s “The Green Berets.” The film has already lent itself well to conservative Clinton-bashing, a great way to alienate both liberal and moderate audiences.

“13 Hours” may be a noble attempt to honor the bravery of those who fought to defend the consulate, but it is naive to think this movie accomplishes that in an apolitical way. Putting politics aside, a movie this flawed does not deserve to be the final word on the current conflict in the Middle East and the Maghreb.