To cry or not to cry: Women showing emotion in workforce slowly changing gender stereotypes

April 17, 2017

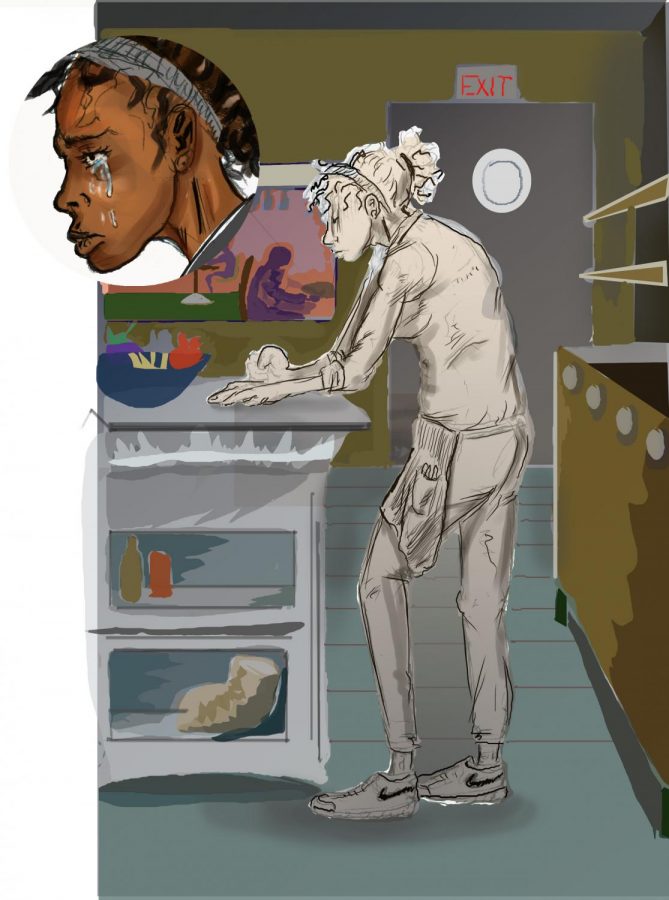

Emotions are part of what makes us human, and Jordyn Nevers knows they aren’t always controllable, especially at work where stress levels are high.

The 27-year-old Chicago advertising art director remembers crying in front of her supervisors during a meeting, which drew unwanted attention. She needed to leave the room and collect herself.

After the meeting, her supervisors didn’t reprimand her but made sure to check in and discover what she already knew: She was a passionate, professional worker who can sometimes let her emotions show. But they were caring and sympathetic, which made her feel comfortable and not embarrassed.

“I try to handle things in a healthy way, but for me, they build up to the point where I get overwhelmed, and it’s very hard not to have a physical response,” Nevers said. “When I was younger, crying was a healthier alternative to doing things that were destructive, passive- aggressive or mean to people.”

True to stereotypes, Nevers said she has witnessed men express anger and frustration by yelling and cursing at work but never with tears. Expressing emotions is natural, but when is it acceptable to show emotion at work and break down in tears, especially for women?

Whether it’s from clients or upper management, breaking down barriers and showing emotions can help people bond and work better together, Nevers noted. She said expressing feelings reminds everyone that “we are not just machines.” Researchers say if people are fairly close friends, then crying at work may be beneficial. However, if they are not, and if people work in open environments, crying could be disruptive to work and lead to negative perceptions of the person crying.

Women crying and showing emotion in the workplace is now a popularized feminist issue. Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg of “Lean In” fame told a group of graduates at Harvard Business School, her alma mater, in 2012 that it’s okay for women to cry at work.

“I don’t believe we have a professional self from Mondays through Fridays and a real self for the rest of the time,” Sandberg told the audience. “That kind of division probably never worked, but in today’s world, with a real voice, an authentic voice, it makes even less sense.”

Sandberg’s stance is proof of changing attitudes, but this consciousness has not spread to every workplace. Any industry that works directly with people, such as the restaurant business and outreach, could be more likely to tolerate emotions. Financial and government institutions could be seen as more strict about showing emotions.

Kevin Snyder, a 22-year-old promotions coordinator at a radio company in Chicago, has observed male colleagues getting angry at work and said he believes it’s more acceptable for men to express anger than for women to cry. He chalks this up to sexism, noting that when men and women express the same emotions, men seem to be better understood and are not negatively labeled.

He admits that if he were to cry in the office, he would try to hide it and not attract a lot of attention because that would make him feel uncomfortable. At the same time, the open environment in which he works creates conviviality and close friendships; therefore, having emotional support is key to succeed on the job.

Criticism of and support for crying at work can’t be discussed without looking at why women cry more than men. According to HowStuffWorks’ science research, “having a good cry” has emotional benefits.

Humans produce three types of tears: Basal tears, reflex tears and emotional tears. Emotional tears contain proteins that release chemicals that build up in the body due to stress, and crying is the body’s method of expelling these toxins. Leucine-enkephalin, one of three proteins found in emotional tears, has been linked to pain reduction and works to improve mood, which is why people can feel better after a good cry. In addition, psychologists found holding in tears is unhealthy and dangerous over time, increasing risks of heart disease and hypertension, the website notes.

Much of this research comes from William Frey, a doctoral professor of neurology at the University of Minnesota who sparked interest in the physiology of tears. In 1985, Frey and co-author Muriel Langseth published “Crying: The Mystery of Tears,” in which he looked at the effect of prolactin in emotional tears. He concluded women cry about four times as often as men because estrogen contains more prolactin.

Research also shows that women and men have different-sized tear ducts: Men have larger ducts, which allow them to hold more liquid before letting them spill, unlike women, who have less control over crying because of their genetic makeup.

There is a predocumented physiological reason for women to cry more frequently than men at work, but women are still seen as weak and manipulative for crying. Those stereotypes hang heavily over most of the workforce, according to Professor Kimberly Elsbach, the Stephen G. Newberry Endowed Chair in Leadership in the Graduate School of Management at the University of California-Davis. Elsbach’s team is one of only a few groups who have been studying the effects and perception of women crying in the workforce.

Elsbach and co-researcher Beth Bechky, a former professor and alumna of the University of California-Davis who now teaches at New York University’s Stern School of Business, found in a 2011 study that crying at work is acceptable in a few situations, such as when a death in the family or divorce occurs. Even then, if crying is excessive or prolonged rather than occurring only once, the person may be labeled as weak, disruptive and manipulative because of the assumption that women get what they want by crying. Elsbach said surprisingly, women observers—in addition to men—viewed other women as manipulative when crying excessively or in the office space.

Elsbach said the perception of women who cry as being manipulative is uncommon but a career-killer. The researchers relatively found that crying during a meeting or an individual performance evaluation with one’s supervisor can have the greatest negative impact.

The researchers just completed a study awaiting publication titled “How Observers Assess Women Who Cry in Professional Work Contexts.” The team found 65 people—split evenly between males and females—who reported 100 stories of recent crying at work they observed within the last year.

The study found four types of situations that induce crying at work: performance evaluation; personal issues such as death, illness, divorce; work-related events such as promotions or assignments; work stress and heated meetings.

Each situation had informal rules governing what behavior was perceived as acceptable. Elsbach pointed out that if women cried within the context of their expected role in the office, it was more likely to be seen as appropriate compared to someone who did not conform to the expected role and acted out of character, like crying in a public setting that disrupts the work of others, usually following a critical performance evaluation.

“People had clear expectations about how they needed to behave even in these stressful, difficult situations at work,” Elsbach said. “As long as you did what you were expected to do, even if it included crying, then you were sort of forgiven.”

These situations strongly apply to office and industry jobs, but for work that is more social and physically strenuous, such as the restaurant business, crying in the workplace is more normal and perhaps accepted.

Maddie Rehayem, a 23-year-old employee at the Chicago Diner in Logan Square, is expected to assist other staffers, run food, bus tables and make milkshakes in an efficient and friendly manner. Rehayem, who has been working there for about a year, said the work environment is often stressful and overwhelming, as it is in any restaurant, which sometimes brings her to tears from anger or frustration. She said it does not interfere with her work and not many coworkers know because it’s a personal matter. She said typically she cries in the bathroom when she needs a break.

“Sometimes I tell people I am a huge crybaby, and people don’t believe me because they think I am really tough,” Rehayem said with a laugh.

For her, crying during stressful times is a release of energy that helps carry her through the work day. Rehayem said she thinks that women are not more emotional than men and the stereotype stamping women as strongly emotional is not accurate; although, she said sexism at her job exists.

“It’s something I’ve struggled with, but you just have to power through it,” she said. “I am an emotional person, but that doesn’t have anything to do with my gender.”

In the corporate world, promotions and layoffs are guaranteed to trigger tears, so it comes as no surprise that human resource professionals witness an array of emotions. Patricia Rios, Columbia’s former associate vice president of Human Resources, now works at the Chicago Housing Authority as the chief administrative officer and oversees the HR department. She has witnessed countless tears shed and other forms of emotional expression in her career. She added that said women and men get treated differently for crying.

“A man could cry and people would not give it a thought,” Rios said. “The next day when a woman cries, they are now stereotyped and labeled.”

To move forward and change the stereotypes surrounding women expressing emotion at work, Elsbach said women must be careful not to confirm it.

“The notion of men being emotional just isn’t there,” she said. “If they do cry, it doesn’t fit any of the stereotypes, so there isn’t that automatic activation. Then people have to do more purposeful thinking,” she said.

Rios stressed that the main goal of everyone in the workforce is to be professional and control their emotions, but she understands it’s difficult. She said it does not hurt a career or change the perception of women to see them crying. If the tears come, she said it’s best to simply embrace them.

“If it happens, don’t apologize for it,” she said. “It is just a show of your emotions.”