Chicago is strengthening its fight for safer food sanitation methods with new measures to catch unhealthy restaurants.

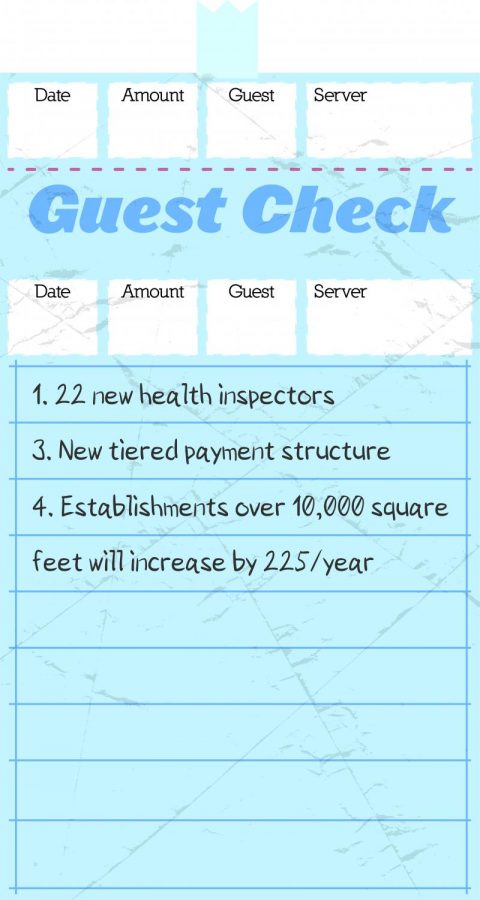

Twenty-two more food inspectors, or sanitarians, will be added to the city’s current total of 38 in the next two years, according to an Oct. 27 mayoral press release.

The cost for the new inspectors will be passed on to larger restaurants through a three-tier licensing fee. Only establishments larger than 10,000 square feet will be subject to a $225 licensing fee increase from the original $1,100 fee. Food venues—such as taverns, diners, grocery stores and restaurants—will also be subject to an increased mandatory re-inspection fee of $50–$100, but the initial inspection will remain free.

“When we are hearing about more and more rats in the city, we need to make sure we [are] hold[ing] our restaurants and groceries up to a pretty high health standard,” said Daniel Block, a professor of Geography at Chicago State University and member of the Chicago Policy Food Action Council.

Chicago has more than 13,500 food establishments, which include restaurants, taverns, grocery stores, bakeries and convenience stores. All institutions are inspected by the current 38 health inspectors at different rates year round.

Places with riskier food-handling practices can be subject to two inspections per year, while others may be inspected once every two years. Inspectors must also follow up on customer complaints throughout the year.

From Nov. 1–14, 58 restaurants, taverns and other eateries failed inspections from the Chicago Department of Health, according to the Chicago Data Portal.

“I have noticed some sub-par cleanliness standards in some [Chicago] restaurants, but nothing that’s turned me off from them,” said John Villarreal, a junior audio arts and acoustics major who spent seven months as a line cook for Mexican-chain-restaurant Qdoba in Minnesota. However, if people took a deeper look into some kitchens, they would see some health code violations, he added.

Chicago has lacked sufficient health inspectors since it showed a need for more sanitarians in a 2016 audit by the city’s inspector general. The audit revealed the city was about 56 inspectors short to adequately inspect all its food service businesses, as reported Dec. 12, 2016, by The Chronicle.

Although 22 new inspectors are only half of the amount recommended by the inspector general’s audit, the increase will help bridge the gap, primarily by inspecting smaller establishments, according to Block.

“I don’t think they are meeting the mandated frequency, at least for many of the small grocery [stores], and I assume that’s true for restaurants as well,” he said.

Yasmin Gonzalez, general manager of Pauly’s Pizza, 719 S. State St., said she supports the increase in health inspectors and is ready for an inspection at any time, adding that the restaurant has never failed an inspection. The restaurant has nightly cleaning, and employees are up to date with the health code certifications and requirements, she added.

The increased number of inspectors will also help Chicago better meet the state and federal requirements for inspector staffing.

“If you can make [health inspections] a more regular thing, people won’t try and get around [the health code] as much,” Block said.