Illinois criminalizes ‘revenge porn’

Revenge Porn statistics

January 25, 2015

Former Gov. Pat Quinn signed legislation on Dec. 29, 2014, that criminalizes “revenge porn,” the public posting and sharing of nonconsensual, sexually explicit images to the Internet.

The law was created to combat the growing epidemic of cyberbullying, according to a Dec. 29 Illinois Government News Network press release. The distribution of private, sexual content without the consent of the participant will result in a class 4 felony starting June 1, and it is punishable by one to three years in prison and up to $25,000 in fines.

Illinois has joined California, New Jersey, Arizona and 13 other states in criminalizing revenge porn, said Mary Anne Franks, associate professor of law at the University of Miami School of Law and legislative and tech policy director for the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative.

Franks has worked with legislators in 22 states, including Illinois, for the past year to draft laws against revenge porn. She said the Illinois law is the strongest nonconsensual pornography law to be passed thus far.

“What we are trying to do with the laws that we are advocating is to get people to understand just how vicious [revenge porn] is and how it is very much like any other form of sexual abuse,” Franks said. “I have worked with drafters to make sure [the law] is narrow, precise, effective and that they comport with the First Amendment.”

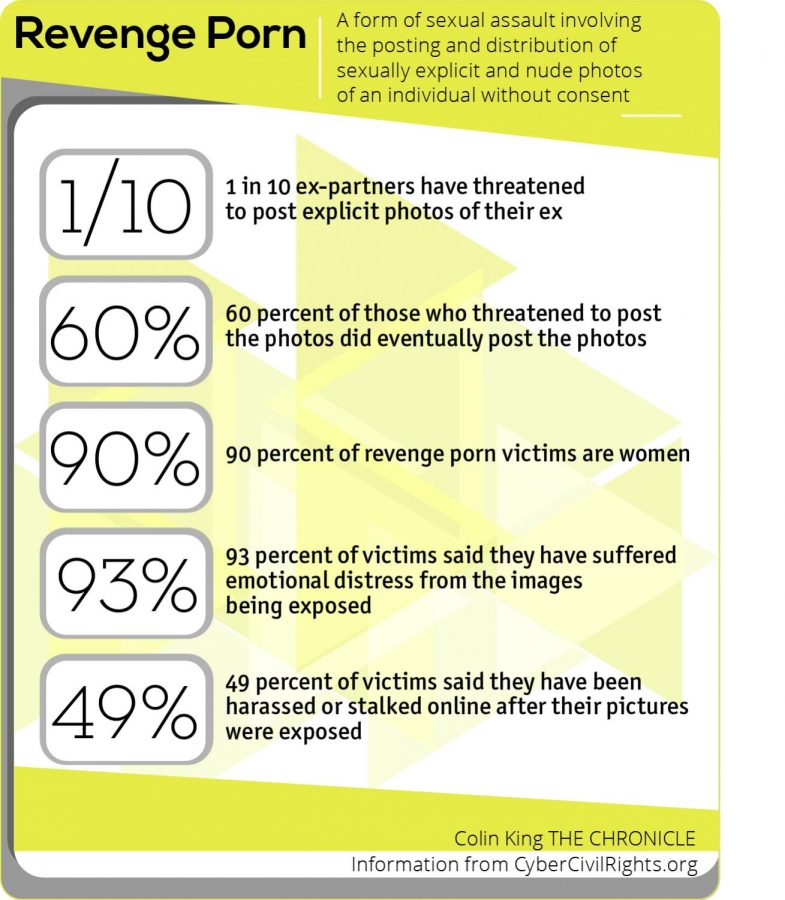

Ninety percent of revenge porn victims who participated in a CCRI survey were women, and 93 percent said they have suffered significant emotional distress after their photos were posted, according to a Jan. 3, 2014, CCRI blog post.

Victims endure further harassment because their photos often go viral, spreading through social media and onto different websites. Photos are also published alongside personal information such as email addresses, phone numbers and home addresses, said Carrie Goldberg, a Brooklyn-based attorney who works with the CCRI and operates her own firm, C.A. Goldberg, PLLC.

“Revenge porn is extremely harmful to the victims,” Goldberg said. “It is on the spectrum of domestic violence. Additionally, it’s harmful because it severely impacts [victims’] Google search results. In the U.S., we don’t have the right to forget. We don’t have control over our search engine results.”

Annmarie Chiarini, a Maryland resident and victim advocate for CCRI, was twice a victim of revenge porn and was diagnosed with both post-traumatic stress disorder and depression prior to a suicide attempt after an ex-boyfriend posted her private images in 2010 and 2011.

“My experience has affected me in two very separate ways,” Chiarini said. “On the one hand, it brought me to the lowest point of my life where I attempted suicide. There was no real moment of rebound or moment of realization where it’s like, ‘Oh life is great and I want to live.’”

Chiarini said she decided to advocate for stricter nonconsensual pornography laws when she realized they were nonexistent in Maryland, although rigorous guidelines have since been established She said she found her voice and strength through advocating for CCRI.

“My case was closed and I could not fight for myself,” Chiarini said. “That didn’t mean that I had to walk away and hide my head in shame. What it meant was that no one else should have to go through what I went through or suffer the way I suffered. If there is anything I can do about it, I’m going to try.”

Illinois State Representative Scott Drury (D–Highwood), a co-sponsor of the bill, said he hopes other states will follow suit in implementing similar laws.

“The ultimate goal is that the federal government will come in and implement a federal law that can regulate conduct across state lines,” Drury said.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois, a foundation dedicated to protecting constitutional rights, has opposed parts of the legislation because it may interfere with the First Amendment, said Ed Yohnka, director of communications and public policy for the ACLU of Illinois.

“Unfortunately, the bill still does not require that the person has the intent to do harm nor that the individual whose image is shared actually feels the harm,” Yohnka said. “For those reasons, we were still opposed to the bill. I think we should be very careful about these things when we talk about bills that carry a criminal penalty. ”

Although improvements to the legislation made throughout 2014 have given the law more precise guidelines, Yohnka said the bill still lacks an intent standard, which may criminalize the people viewing the images instead of the posters.

Franks said the statute gives clear guidelines for images that are accidentally and intentionally posted and that while the harm requirement is not spelled out in the bill, the same is true of other voyeurism laws that protect an individual’s privacy. She added that nonconsensual pornography legislation is as necessary as other privacy laws and that criminalizing the posting of sexually explicit images will help decrease instances of that behavior.

“If we imagine a society where rape is not punished by the criminal law, you can certainly imagine how people in that society would not think of sexual violence as a bad thing because it would not be criminalized,” Franks said. “That doesn’t mean when you criminalize something that people stop engaging in sexual assault, and it doesn’t mean that they stop blaming the victim.”