Minorities suffer from polluted communities

April 28, 2014

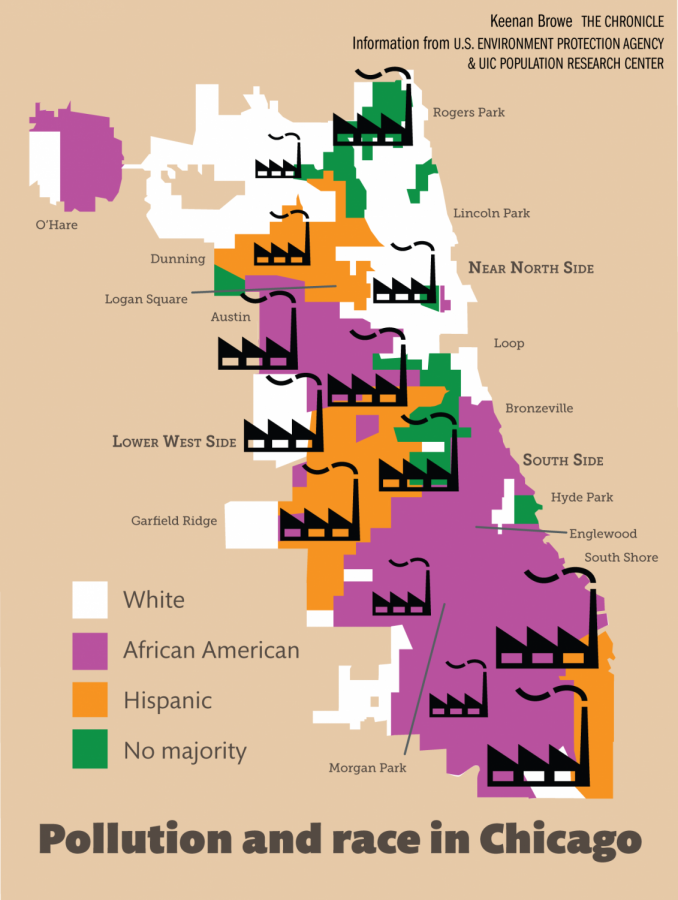

Chicago communities with large minority populations are more likely to experience poor air quality and high levels of pollution, according to a recent study.

The report, released April 15 by the University of Minnesota, found that minorities are exposed to air with 38 percent higher levels of nitrogen dioxide outdoors than residents in predominately white areas, which can be to blame for thousands of premature deaths, according to the study.

The study ranked Chicago as the urban area with the 12th largest exposure gap between whites and non-whites. Illinois clocked in with the third-largest exposure gap.

Pollution caused by nitrogen dioxide, which enters the air through exhaust fumes and

power plants, can be linked to asthma and heart disease. It causes about 7,000 deaths a year, according to the study.

Lara Clark, author of the study and student at the University of Minnesota, said other studies dating back to the 1970s show communities made up of low-income residents are exposed to 38 percent more polluted air than affluent communities with a white racial majority. She said the improved availability of air pollution data inspired her to conduct the study.

“It wasn’t surprising to see disparities in exposure because that’s something that has been seen in a lot of studies,” Clark said. “What did surprise me was that it’s a problem that exists even in cities that have relatively clean air.”

Faith Bugel, senior attorney for the Environmental Law Policy Center, said it is inevitable that some low-income minorities will live in heavily polluted areas because they lack the financial means to relocate to cleaner areas.

“Some people don’t have economic flexibility in the choice of where they live,” Bugel said. “If an apartment next to the highway costs less than an apartment next to the park, then you might be picking the one next to the highway because you just don’t have the choice.”

Ted Pearson, co-chair of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, said large corporations can set up power plants in minority-occupied areas and often target these communities because residents do not have the clout to fight back.

“The economics of capitalism are such that poor people get screwed because the system is so weighted with racism and white supremacy,” Pearson said.

The ELPC has been advocating to reduce levels of nitrogen dioxide in the city’s minority communities, Bugel said, adding that 13 years ago the ELPC closely examined Chicago’s coal-fired power plants and their impacts on residents’ health. After spending more than 12 years working with 55 organizations, the ELPC was successful in shutting down two Pilsen coal power plants in 2012, Bugel said.

“This is something that matters to us for environmental justice reasons, but also because this is where we live and work too,” Bugel said. “It is a public health concern, too.”

But just because a power plant closes, it does not guarantee that the air is clean, said ELPC media relations manager, David Jakubiak.

“We’re not going to shut down a coal plant and all of a sudden end asthma in Pilsen,” Jakubiak said. “At the same time, if you know there is an issue, you want to take every step to minimize those risk factors, and that’s why it’s important [to close such facilities].”

Pearson said state officials often ignored residents’ complaints when they reported experiencing side effects of pollution exposure.

“They justify their tolerance of polluters [because] they create jobs and economic development,” Pearson said.

Bugel said Mayor Rahm Emanuel and various aldermen have been supportive of the Chicago Clean Power Ordinance, which shut down Pilsen’s coal-fired power plants. However, she said the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, which is tasked with regulating Illinois’ air quality, has not been active enough in addressing air pollution.

“In my experience in working with IEPA, I am disappointed,” Bugel said. “Unfortunately, when you make an argument about public health, respiratory [health] and premature mortality, they never seem to respond to those concerns.”

The IEPA did not respond to requests for comment as of press time.

Pearson said he believes that if community members and city officials pressure state legislators to take a stance against environmental injustice, they will act.

“Folks may get weary, but you have to keep fighting the good fight.” Jakubiak said. “Keep pushing as hard as you can. That’s the only way we are ever going to get anywhere.”