Bursts of fasting may be key to longevity and health

Bursts of fasting may be key to longevity and health

March 9, 2015

Hunger. People go to great lengths to keep their stomachs full, but research dating back more than 60 years suggests that temporarily depriving oneself of food may be the key to a long and healthy life.

Clinical research from as early as 1945 reveals that restricting calories in animal test subjects results in a longer life—up to 20 percent longer in mice—and significantly decreases the likelihood of developing age-related disease. At the time the researchers might not have known the mechanisms behind the disease-fighting and life-extending qualities mustered by the missing calories, but recent science has suggested a handful of potential answers for why an energy-scarce environment might result in

health benefits.

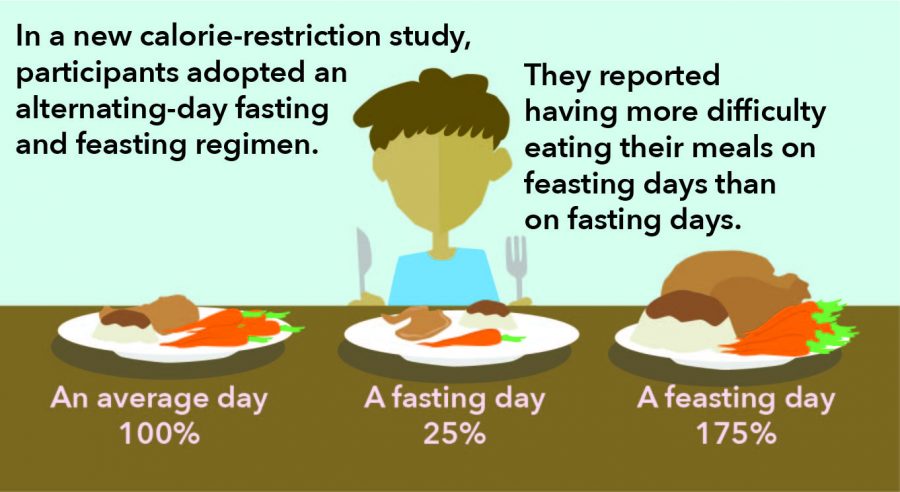

In a February 2015 paper published in the journal Rejuvenation Research, scientists from the University of Florida recruited a group of healthy individuals to fast intermittently for two three-week periods. On “fasting” days, the group had their caloric intake restricted to 25 percent of their average diet. Conversely, on alternating “feasting” days, they were required to eat 175 percent of their normal intake to control for fluctuating weight as a confounding variable. Researchers hypothesized that this intermittent fasting approach might be a more sustainable eating pattern for the long-term than a consistently calorie-restricted diet.

“Most of the evidence in terms of caloric restriction in humans is typically in an observational context where you have people who choose to do it because that’s the kind of lifestyle they want to live,” said Martin Wegman, the lead author of the study and an M.D.-Ph.D. student at the University of Florida. “There’s anecdotal evidence in those arenas that those who [fast] tend to slow down some aging-related diseases, tend to live longer.”

When cells in the body shift from an energy-rich environment to an energy-poor environment, like when the energy stored from food runs out, it produces reactive oxygen species—or chemically reactive oxygen-containing molecules—Wegman said. Researchers suspect the presence of these molecules creates stress in the cell that promotes the genetic changes that result in a kind of cellular-protective action, including the production of antioxidants in the body.

“We’ve postulated that in certain scenarios they can actually serve a beneficial role in many different pathways,” Wegman said. “We’re considering whether or not the intermittent fasting regimen may be an effective way to upregulate [reactive oxygen species] intermittently to trigger a kind of

protective mechanism.”

Post-study blood tests showed that certain genes, which have been linked to anti-aging characteristics, were expressed in greater numbers while circulating insulin decreased. The study also included a dietary satisfaction survey component.

“That’s actually one of the bigger surprises,” said Michael Guo, co-author and graduate student in the Hirschhorn Lab at Harvard Medical School. “On one day someone is fasting at 25 percent of their normal intake and on feasting days eating 175 percent of normal caloric intake. We expected the fasting days to be more difficult but found it to be exactly the opposite. Participants had more trouble eating the full 175 percent and found little trouble with the fasting days.”

According to Mark Mattson, chief of the Laboratory of Neurosciences at the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore, Maryland, the surprising ease with which participants ate so few calories on fasting days may have an evolutionary adaptive basis, which could explain the resulting health benefits.

“In pathological conditions, there’s an abnormal accumulation of damaged and dysfunctional proteins in the cells,” Mattson said. “What’s happening is that fasting and calorie restriction and exercise activate a pathway called autophagy—an old term meaning ‘self-eating.’ It’s a mechanism whereby cells remove garbage and that protects them from building up these damaging proteins. It also increases the production of neurotropic factors which we’ve seen lead to cognitive improvements in animals.”

Intuitively, our ancestors did not have a constant supply of food and would have likely fasted for extended periods of time, Mattson said. When we eat three or more regular meals per day, our livers primarily store energy as glucose. Mattson said it takes at least 10–12 hours of fasting to deplete those stores before the body uses fatty acids from cells as energy, which can translate to weight loss, improvements in body composition and, possibly, cognitive benefits.

“We think that intermittent fasting is superior to counting calories at each meal or eating regular smaller meals,” Mattson said. “During the fasting period you activate the garbage disposal mechanisms, the neurotropic factor mechanisms, the mechanisms that suppress inflammation. When you do eat, when you catch your prey, your cells are ready to grow and function better. We think cycles of mild stress-and-recovery—which is kind of what the evolutionary situation was—might be better for health than a more constant intake of calories.”