Art conservation gets laser treatment

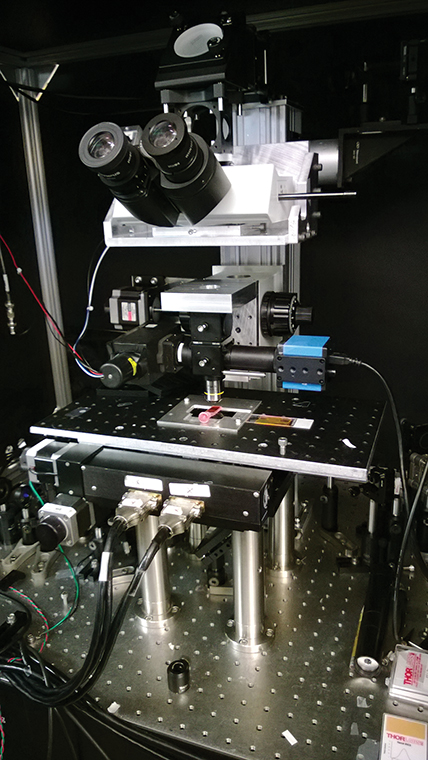

Pump-probe microscope

February 3, 2014

Chipping away at paintings with a scalpel is the conventional way to study pigments used in a piece of art, but researchers are developing new, noninvasive methods to replace this art conservation technique.

Methods in conservation have become more sophisticated over time, according to Rolf Achilles, curator at the Smith Museum of Stained Glass Windows and an adjunct faculty member at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Today, art conservators use certain liquids such as distilled water to clean artwork without damaging the pieces.

“It used to be you could clean a painting just by smudging some cigarette ashes on it and rubbing across it,” Achilles said.

But not anymore. The latest development in conservation technology was explored in a December 2013 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It detailed a custom-built, pump-probe laser microscope that was used to explore the molecular properties of Puccio Capanna’s “The Crucifixion.”

The machine uses intense laser pulses shaped like a picket fence to measure different molecular signatures that absorb light in a way that cannot be gathered with conventional methods, according to Warren S. Warren, a Duke University professor in chemistry, radiology, physics and biomedical engineering.

“People paint with things that absorb light,” Warren said. “If you can use a method that exploits the contrast that you get with visible or near-visible light, you’re going to be getting out contrast, which is more relevant to understanding what the artist actually did.”

Other advanced techniques such as X-rays, infrared and ultraviolet photography have been used to study paintings, but they do not give any 3D information for pigment composition, according to Tana Villafana, a Duke graduate student and senior research assistant.

“Figuring out that kind of composition is really important in studying paintings particularly,” Villafana said.

Apart from paintings, Warren hopes to extend the use of pump-probe microscopy to pottery, such as terra cotta, and manuscripts that cannot be unrolled.

The research team is also creating a database of pigment responses to the microscope in various paintings.

The most important benefit of this method is that it is noninvasive, according to Villafana.

“So far, everything that we’ve done has been visually nondestructive,” Villafana said. “Of course, sometimes with pigments, in order to say something was completely nondestructive we’d have to go back after 50 years and make sure that no degradation has occurred.”

There are drawbacks to using pump-probe microscopy, including a high operation cost and immobility. But the research team is working to build a smaller, portable system, Warren said. The method does not replace the process of cleaning a piece of art.

“Whenever you start removing grime from something, it’s not only the grime that you’re taking off, it’s also taking off a microscopic layer of whatever’s underneath the grime in all probability,” Achilles said.

Researchers are continuing to improve methods that allow lasers to clean delicate works of art. Lasers have already been used to clean the exterior of buildings such as the Driehaus Museum in Chicago and medieval churches in Germany, according to Achilles.

“It took months and months and cost an enormous amount of money … but the results are just amazing,” Achilles said. “[It] allows you to restore or repaint the building in a way that you would’ve never thought possible before the laser invasion.”

These new methods for studying and conserving art are being taught in art history curriculums across the country, according to Achilles. Warren is teaching a course at Duke this semester on the pump-probe microscopy method.

Art deteriorates over time and in order to preserve it for future generations, it needs to be taken care of, Achilles said.

“The way to do that is to conserve it, to restore it,” Achilles said. “Not to embalm it but to take care of it.”