Turning back the clocks

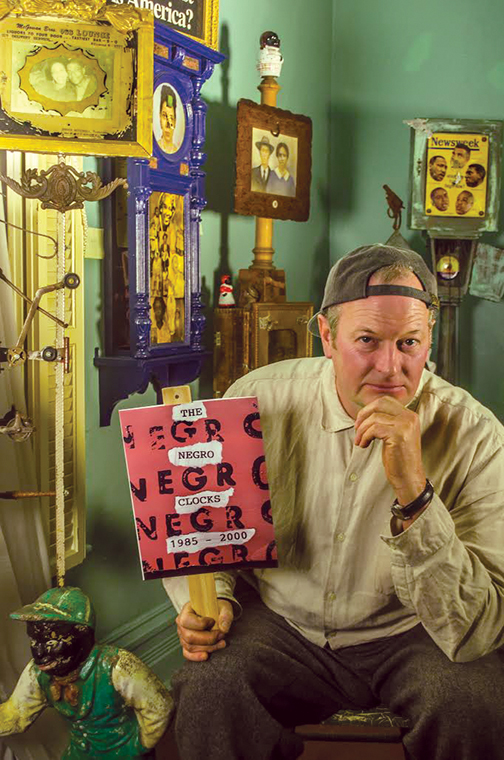

Local artist John John faces racism head on with his “Negro Clocks.”

February 17, 2014

The loud, manic ticking of unsynchronized cuckoo clocks bombards viewers as they take in “The Negro Clocks,” local visual artist John John’s newest exhibition, which opened Feb. 7 at the Jennifer Norback Fine Art Gallery, 217 Huron St.

The exhibit explores the United States’ relationship with racism, as well as the personal connection John John, a white gay male, feels to intolerance. As a young person, John John said he was often the victim of bullying and name calling for his looks and sexuality.

All told, John John has designed 16 ornately garnished cuckoo clocks using racist images from early 20th century American pop culture. Six of the clocks are in the exhibit, and their stereotypical portrayals of black people shed light on current racial issues.

“The Negro Clocks’ purpose is not to tell time,” John John said. “The whole purpose is to have the cuckoo come out as often as possible. The cuckoo for me is indicative of madness and craziness in regard to racism.”

Using collected materials such as Confederate money, a 1921 “Little Black Sambo” bowling game, Aunt Jemima pancake mix, newspaper clippings and even photos of his grandparents standing next to performers in blackface, John John’s clocks juxtapose modern and antiquated imagery in a collage representing racism’s persisting presence in contemporary society.

The word “negro” is stamped on nearly every clock. Handheld signs reading “Negro Clocks are Against the Law” and “Negro Clocks are our friends” are available for guests to take.

The project began in 1983, when a young John John, frustrated with his hectic lifestyle in America, escaped to Paris, where he found inspiration in the form of a cuckoo clock during a trip to a flea market.

The clock, similar to one in John John’s childhood home, stirred up old memories of the Civil Rights movement flashing across his parents’ television set in the early 1960s. Growing up as an outsider himself, John John identified with the struggle of black Americans.

“[When] I was very young and handsome [I] was still suffering a lot from strangers in the street calling me f—-t and queen,” John John said. “I had people coming up to my breakfast table telling me I was going to hell.”

Blending his personal experiences of marginalization and his observations of black persecution, the “Negro Clocks” were born. John completed one clock every year from 1984–2000, representative of his racial experiences in that time period.

Gallery owner Jennifer Norback thinks it is impossible to talk about race without talking about time. The clocks are indicative of that, Norback said.

“Whether it’s using a word like Negro, you’ll find an older person saying, ‘We used to use that word but we don’t anymore,’” Norback said. “Slavery wasn’t that long ago … it’s something that’s so intrinsically a part of the American experience of racism.”

John John is challenging his viewers by handling racially charged subjects because many people may think he lacks the authority to do so, Norback said.

“It’s all the more uncomfortable because [John John is] using these images as a white man. I think that we don’t feel in a sense that he has the right to do that,” Norback said. “But in fact these are all images that have come to him; these are a part of his history.”

Gallery assistant Mark Toriski, who markets and publicizes the artists for Norback’s gallery, created a book showcasing all of John John’s clocks.

“We knew that having 16 of these clocks wouldn’t realistically and spatially work within the gallery,” Toriski said. “He had never before organized these chronologically because he did one clock per year … he always wondered if they would tell a story. Now, with [the] ‘Negro Clocks’ book, he’s finally realizing that the ‘Negro Clocks’ do tell a story.”

John John said he was overjoyed with the book.

“The last words in the book were, ‘I always had full confidence in my ‘Negro Clocks,’ and I still do,” John John said.

American Academy of Art student Nikalette McComb, a photographer and freelancer, was commissioned to photograph John John’s clocks for Toriski’s book.

“I was only like the third person to ever see these clocks and when I saw them I was mind-blown at first,” McComb said. “I wanted to stay and photograph them for hours.”

Sheila Baldwin, a Columbia professor of English and African-American studies, thinks understanding the kinds of stereotypes on display in the Negro Clocks exhibit is key to eliminating bias.

“[John John’s work was] very shocking to look at,” Baldwin said. “Those kinds of images help you see things in a different light.

The kinds of images [John John has] are so wonderful to see because they do spark conversation.”