Dolls like me: Creating dolls that break the mold

January 29, 2018

Yelitsa Jean-Charles remembers when, as a child, she cried when her parents gave her a black doll because the doll wasn’t white, and that she used to place scarves on her own head to pretend she had long, flowing hair.

Jean-Charles said she struggled to understand her identity and why her dolls didn’t represent the beauty she saw in her own friends and family. This lack of representation and other childhood experiences clouded Jean-Charles’ idea of beauty.

“I remember coming back from my trip to Florida and my family members didn’t ask about how was Disney World, and what you did and what you ate. They turned to mom and they said, ‘Why did you let her get so dark?’” Jean-Charles said. “I remember avoiding the sun, I straightened my hair all the time because I did not like my naturally kinky hair, and that didn’t stop for a long time, and I realized, had I had diverse products and representation, I probably wouldn’t have felt that way.”

Now Jean-Charles is sharing her grown-up sense of beauty, individuality and self by being part of a new generation of toy makers who respect and reflect multicultural features in their creations.

Jean-Charles’ idea of beauty changed once she began studying at the Rhode Island School of Design and encountered a classmate who decided to embrace her natural hair, which encouraged Jean-Charles to better understand her own identity.

Another classmate told her it was not an art student’s job to be socially aware and responsible, but Jean-Charles disagreed. She then began a project researching and interviewing other women about their experiences with dolls. In 2014, she was awarded the Brown University Social Innovation Fellowship to start her brand, Healthy Roots, which launched in 2015.

Healthy Roots is an online toy company that creates dolls and storybooks that teach children about natural hair care. Jean-Charles said the company’s goal is to combat internalized racism by creating diverse dolls. The Healthy Roots characters feature a range of skin tones and hairstyles, including braids and afros. For example, an 18-inch doll named Zoe has a darker complexion, fuller lips and long, tightly curled hair—much different than the classic white Barbie.

Jean-Charles said she thinks her sense of aesthetics would have evolved differently if she had diverse dolls as a child and hopes to provide better examples for the present generation of children, which she experienced during a recent photoshoot.

“I almost cried because one of the little girls, she walks in and she sees me holding the doll and she just runs up to me, she goes, ‘Wow.’ That’s all I needed to hear to know that this product is doing what it’s supposed to do,” Jean-Charles said.

Unlike Jean-Charles, 27-year-old Samantha Knowles was surrounded by diverse toys given to her by her parents in the predominantly white town of Warwick, New York. Knowles’ mother would special order black dolls during Christmastime because, despite their shortage on store shelves, she believed it was important for Knowles to have diverse toys.

But she recalls being 8 years old when a white playmate asked, “Why do you have black dolls?”

“To her, it was something that was odd,” Knowles said. “I don’t remember how I responded to her in that moment, but then years later when I was a senior in college and thinking of ideas for my senior honors thesis, that question popped into my head and I thought, ‘I need to explore this.’”

Knowles calls this an “othering” question, one of many she remembers being asked by her peers that indicated their differences.

“Questions about your hair, your background, where your parents are from, all of these questions that really point to how different you are and that can be grounds for rich discussions, but when you’re a kid, it can feel like you’re being othered,” Knowles said. “It was one of those questions that I felt like I had to dodge or gloss over because it’s hard to navigate as a kid.”

In 2012, Knowles directed the film “Why Do You Have Black Dolls?” that captured the story of a small community of women who collect and create black dolls.

“[These dolls] were respecting beauty, and not beauty in terms of this cookie cutter, conventional standard. They were reflecting all different types, but of black people, which is not always readily available,” Knowles said. “They were these political things created in reaction to what they felt was inadequate.”

Doll companies both big and small have begun to increase the diversity and individuality of their dolls—including ethnicity, body types and other characteristics—as the demand grows, stemming from the country’s increasingly diverse population and awareness.

In April 2015, Barbie—the famous American doll manufactured by Mattel Inc.—announced its Shero line, which honored six inspiring females that break boundaries and open up opportunities for women. Continuously expanding since then, the line released its tenth doll in November 2017, modeled after Muslim-American Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad. It was the first Barbie doll to wear a hijab.

While some toy companies have previously attempted to make diverse dolls, production of multicultural dolls has posed a problem as some companies adhered to stereotypes.

The first black Barbie, released in 1980, had brown skin but the same face mold as white Barbie, a move that was criticized by consumers who did not think black Barbies should share the same physical features as white Barbies.

The Barbie Dolls of the World collection, released in 2013, featured several dolls in traditional outfits from different countries, each carrying a passport and an animal from their home country, reinforced negative stereotypes with inauthentic costumes.

Debra Britt, founder and executive director of the National Black Doll Museum in Mansfield, Massachusetts, said mistakes are more likely to happen when people of color are not involved in the development process.

While Britt appreciates multicultural dolls from brands such as Barbie and American Girl, she said dolls of color that come with individual storylines—such as American Girl dolls named Addy and Gabriela—often do a disservice to children who play with them and can send them a different message. Addy, released in 1993, is a doll who was born into slavery in the 1800s but escapes to freedom. Gabriela, who was named the company’s 2017 Girl of the Year, has a stutter.

“Every time they produce a doll of color, we have to have some kind of issue; we just can’t be a doll, we just can’t be great. We have to come with storylines that we’ve had to fight something,” Britt said. “There’s more to people of color than us just struggling. We’ve overcome a lot but we already have great characteristics about ourselves.”

Knowles agreed that dolls of color should not be made to look the same as white dolls, but said she still appreciates that the dolls exist at all.

“That’s a good thing if you have dolls that are made by individuals who are making them look like a lot of different types of people, but I also don’t want to criticize companies who are finally making these dolls and finally American Girl has more than just the Addy dolls,” Knowles said. “There are criticisms that come with the Addy dolls, but it’s good to have those mainstream dolls existing, and I would love to see more types of dolls that sort of represent people in all different types of ways.”

Stacey McBride-Irby worked for Mattel for 15 years, during which she increased Barbie’s diverse collections. In addition to putting her take on the 1980s black Barbie, she also designed the Sorority Barbie in 2008 to celebrate the centennial year of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the first African-American Greek Sorority. In 2009, McBride-Irby created So In Style, a line of African-American Barbie dolls with realistic physical features.

McBride-Irby decided to leave Mattel in 2011 to co-found the One World Doll Project, which launched the PRETTIE Girl doll company in 2013, a collection of multicultural dolls that come with individual stories.

McBride-Irby said it is imperative for dolls to reflect the country’s increasingly diverse population, which inspires her to create each doll. McBride-Irby also added that it’s important to have diverse doll designers at each company in order to avoid controversy throughout the design process.

“The thought process would basically be what’s needed out there [and] what speaks to my heart,” McBride-Irby said. “When I design my dolls, I come from the community, and I’m African-American so I’m more aware of what to do and what not to do.”

The Heart For Hearts Girls doll company currently has dolls made to represent girls from several countries, including the United States, Ethiopia, Mexico and India. It also has dolls representing Afghanistan and Native Americans coming out this fall, according to Sales Manager Alyssa Prince.

The dolls come with their stories and backgrounds inspired from each doll’s country. The company also donates a dollar from each doll purchased to World Vision, a global organization dedicated to supporting children with local programs.

Prince said it takes about a year to create each doll, including the design process and the time it takes for researchers to research each culture to assure each doll and story is authentic.

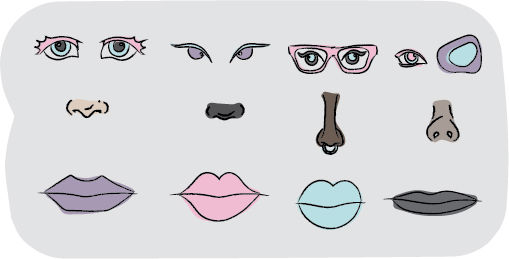

“We want to make sure the stories are authentic [and] realistic, but also child-appropriate,” Prince said. “Each doll has a different face mold so everyone looks a little different. They have a similar look to them, a young girl face, but we definitely did take a lot of consideration looking into different features that came out one region and tried to bring out those features that were very important to represent a region.”

Amy Ewaldt, an adjunct professor in the History, Humanities and Social Sciences Department and 2008 early childhood education alumna, is the owner and director of Cortland Preschool, 1859 N. Talman Ave. The preschool, Ewaldt said, includes a variety of dolls for children, both nongendered and gendered and those with different hair types and ethnicities.

“They start to notice that there are different kinds of people in the world and they’re curious about that. They see it as a very natural and easy thing to ask questions about,” Ewaldt said. “They’re so accepting of who they are and who their friends are and it’s about them having themselves reflected in the materials around them but also having an accurate representation of the city we live in too.”

Dolls are the ultimate visual representation because they are made to look like a human, Knowles said.

“It’s very positive for a child to see themselves represented in a positive way, especially if that child is part of a group of people who historically have not been represented positively,” Knowles said. “It’s just one additional thing you make available, a positive representation of a person of color especially at a young age, a formative age for them to see themselves reflected in something positive.”