Initiative works to eliminate HIV in most-affected group

October 2, 2017

When Erik Glenn, executive director of Chicago Black Gay Men’s Caucus, first came to Chicago when he was 22, he knew almost nothing about HIV. He was a gay, sexually active man who assumed he had already contracted the disease because of who he is.

Glenn’s organization is now one of many groups collaborating with the Getting to Zero initiative, a statewide effort to wipe out new HIV diagnoses in 10 years.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced his support for the program in a Sept. 19 press release, which will increase prevention medication use such as PrEP—a daily pill that reduces HIV infection risk by more than 90 percent—among those most vulnerable to HIV. The initiative also aims to ensure that 70 percent of people living with HIV receive the necessary medication to reduce their viral load, which significantly reduces the risk of transmission.

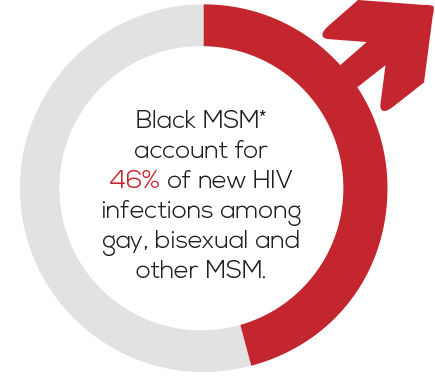

For two years in a row, Chicago has had fewer than 1,000 new HIV diagnoses per year for the first time in 20 years, said John Peller, CEO and president of the AIDS Foundation Chicago. However, nationwide, black gay men are disproportionately at risk for HIV and account for 46 percent of new infections among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men.

“While it’s tremendous new cases have dropped significantly, the cases haven’t dropped equally among all populations,” he added.

Peller said research shows black gay men have condomless sex at the same rates as their white counterparts, and their rates of sexually transmitted infections or drug use are also not much different. Factors like racial discrimination and segregation, which lead to a lack of access to health care, contribute to the gap, he added.

Glenn said individuals tend to have sexual contact within their own racial groups, so HIV is concentrated in the community.

“The language that public health uses very often is [that] black gay men are at risk, in danger [or] more likely to get HIV,” Glenn said. “How that gets internalized is as if something [is] wrong with us.”

While medical technology has made it impossible for patients in HIV treatment for at least six months to transmit the disease to anyone else, Peller said the stigma surrounding HIV still exists.

“On gay dating apps, there are still people who ask the question ‘Are you clean?’” Peller said, “implying that people living with HIV are unclean or dirty in some way, which is stigmatizing.”

Along with providing education to end the HIV stigma, the GTZ initiative also aims to bring awareness to preventive medication.

Peller said a 20 percent increase in the utilization of PrEP and a 20 percent increase in the rate of viral suppression will bring Chicago to fewer than 100 new cases of HIV a year by 2027.

While PrEP is covered by most health insurers, Peller said the preventive medication can cost $1,500 per month for those who do not have insurance.

“There is a lot of work that needs to be done to educate people about PrEP and where and how to access it,” Peller said, “particularly among the populations that are most vulnerable to HIV, which [are] people who are low-income and already very marginalized.”

Simone Koehlinger, senior vice president of programming for the AIDS Foundation of Chicago, said she has found it challenging to tell patients they are HIV positive when she gave screenings and counseling at a health clinic. She said she would never forget one patient—a black man in his 20s—who was not surprised to learn he had HIV because he felt it was an inevitable diagnosis.

“Stories like that really call attention to the injustice we see,” Koehlinger said. “It doesn’t have to be that way. No 20-year-old, no matter their race or living circumstances, should be thinking that [it] is just a matter of time [until] they have [HIV].”