How to apologize for sexual misconduct

January 21, 2018

In a Dec. 28 Facebook post, senior theatre major Evan Louis Szewc announced his resignation as creative director for the 2018 Manifest Urban Arts Festival after allegations of misconduct surfaced on social media, as reported Jan. 5 by The Chronicle. In his post, Szewc acknowledged the allegations against him and apologized for his actions.

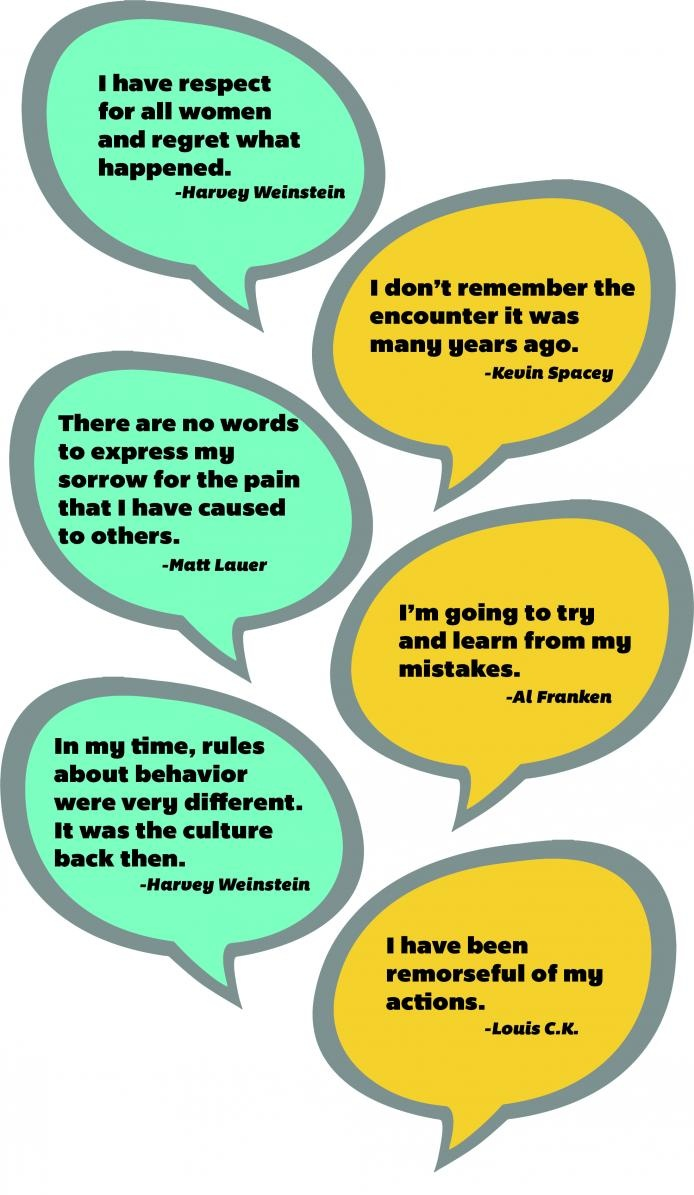

It’s easy to become cynical about apologies as more revelations of sexual misconduct have come to light, both in Hollywood and closer to home. The distressing stories have become exhausting, and the generic apologies even more so, reading as desperate attempts at damage control. The worst examples include Kevin Spacey’s apology in which he claimed not to remember committing abuse and chef Mario Batali’s, which was accompanied by a cinnamon roll recipe.

Is it possible to make an apology that goes beyond mere words and does something to rectify past wrongs? We think so, if the apology is a first step and not a last one.

Step One: Apologize to the victim(s), not the public.

There is no test to measure the sincerity of an apology, but one can’t help but assume that many of the public statements made in recent months weren’t intended for the victims. Instead, many of the apologies read as carefully crafted attempts to salvage public reputations and cut losses.

Comedy writer Dan Harmon, however, is an important example of accepting responsibility and showing respect after Megan Ganz, a comedy writer who worked under Harmon on the television show “Community,” accused him of harassment. Harmon and Ganz had a candid conversation through a Jan. 2 Twitter thread in which he acknowledged and apologized for his abuse of power as Ganz’s boss.

In the thread, Harmon let Ganz lead the conversation. He accepted blame, did not try to deflect responsibility and asked for Ganz’s input on how he should address his misconduct, telling her, “I’ll let you call the shots.”

Harmon went on to discuss the harassment he committed in a Jan. 10 episode of his podcast “Harmontown” and accepted full responsibility. After listening to the podcast, Ganz aptly called Harmon’s response a “masterclass in How to Apologize” in a Jan. 11 Twitter thread before announcing she forgave him.

Step Two: Make amends through actions.

It is easy to say, “I’m sorry.” But showing that you are sorry is a much harder feat. True dedication to redemption takes time, effort and an understanding of the role you played in another’s pain.

In a Jan. 17 Instagram post, actor Timothée Chalamet did not use the word “sorry” when he recognized his role in Woody Allen’s unreleased film “A Rainy Day in New York” as harmful, but his actions perfectly communicated his feelings. Chalamet stated he did not want to profit off of Allen’s film and announced he would be donating his entire salary from the film to the anti-harassment group Time’s Up, the L.G.B.T. Center in New York, and the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

Chalamet’s statement may seem out of place within the Me Too movement. He wasn’t accused of harassment or assault; all he did was play a character in a movie created by a man who was accused. But this movement is more than holding individuals who have committed misconduct accountable, and it is why this final step is crucial for change.

Step Three: Accept that you are part of the system.

One of the most damning revelations that has come from the Me Too movement has been the sheer number of men dumbfounded that their actions were sexual misconduct. In many of these situations victims were left—often visibly—traumatized and the men walked away from the situation, unaware of the number of boundaries they had crossed.

Documentary filmmaker Morgan Spurlock’s Dec. 14 confession, which he announced before any public accusations against him arose, exemplifies the dangerous cluelessness many have fallen into. In his account in which he admitted to sexual assault and harassment, Spurlock details a night with a girl in college who cried while in bed with him, and it never crossed his mind that he committed assault until he was later confronted about the event. Spurlock wrote, “I believed she was feeling better. She believed she was raped.”

As much as Spurlock is to blame for his actions, we must address the reason for his and others’ total misunderstanding of relationships and consent. Our entire society must learn to make amends to the victims it has created because we are all responsible.

There would not be countless abusers that have been able to remain in hiding for years had it not been for widespread complicity. For every serial abuser, there is a devil’s advocate. For every instance of violated consent, an ongoing history of inadequate sex education is behind it. For every man hungry for power, there are generations that prodded him to dangerously wield his power over others.