Exhibit showcases Alzheimer’s through art

The exhibit, titled “William Utermohlen: A Persistence of Memory,” arrived at the museum Feb. 6 and features more than 100 works illustrating the impact Alzheimer’s had on Utermohlen’s creativity

February 22, 2016

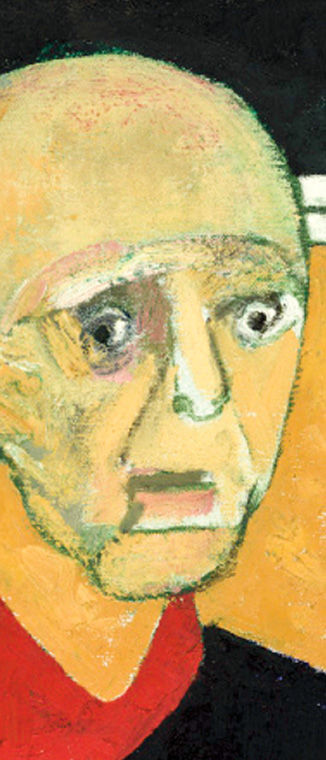

Artist William Utermohlen spent the final years of his life creating art after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 1995.That artwork has since been brought in by Pamela Ambrose, director of Cultural Affairs at Loyola University Chicago, and is scheduled to be on display at the Loyola University Museum of Art until July 23.

The exhibit, titled “William Utermohlen: A Persistence of Memory,” arrived at the museum Feb. 6 and features more than 100 works illustrating the impact Alzheimer’s had on Utermohlen’s creativity.

The exhibit portrays the effects of the disease from beginning to end in his artwork, culminating in the last stages of his life, when the details of his artwork begin to lose their vibrancy, Ambrose said.

“[The exhibit] begins with [Utermohlen’s] very early work, when he was maybe just out of art school, and you can see how his work changed in big blocks,” Ambrose said. “It’s colorful until the last stages, and then he just drew in black and white.”

Natasha Ritsma, curator at LUMA, said the progression looks like Utermohlen is “entering a new phase of his career.”

Utermohlen began having feelings of isolation due to lack of spoken communication, but continued to paint himself and his surroundings, according to the museum’s website.

Those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease are still able to communicate nonverbally, said Theresa Dewey, manager of Care Navigation and Early Stage Engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association’s Greater Illinois Chapter.

“You’re able to pick up on what other people might be saying through their facial expressions or their body language,” Dewey said. “That transfers beautifully over to art.”

She said creating art is helping those who suffer from the disease explore their senses.

“[People with Alzheimer’s] can create something and have it speak back to them,” Dewey said.

LUMA stands in partnership with Northwestern University’s Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center through their “ilLUMAnations” program, which uses art as a method of reaching Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers. “A Persistence of Memory” was proposed as a way to highlight the program, according to Ambrose.

Alzheimer’s disease is a type of dementia that causes problems with memory, thinking and behavior, according to Dewey. The disease is the most common form of dementia and is currently incurable, though there are medications available that can slow the development of the disease’s effects .

Grace Iverson, an education intern at LUMA, said she proposed the student perspective on the exhibit ultimately stems from curiosity and the unknown.

“Utermohlen has something to offer us that we can learn from,” Iverson said. “He wasn’t a 20-year-old in New York and was [still] communicating an important message.”

According to Ambrose, LUMA involves the students in the exhibits as much as possible. Iverson said students’ interest piqued when they heard the story of Utermohlen’s declining health in relation to his art.

“[‘A Persistence of Memory’ is] a lot of interpretation from the viewer,” Ambrose said. “Do we do our best work when we’re old with a wealth of experience behind us, or do we do our best work when we’re young and inspired?”