Not quite history: films that take on real tragedies

Not quite history: films that take on real tragedies

March 27, 2017

Robert Pattinson walks into one of the World Trade Center buildings on 9/11. Ben Affleck serves in the Army Corps when Japan attacks Pearl Harbor. Mark Wahlberg aides a manhunt for the terrorists who detonated bombs at the Boston Marathon.

It’s not a rare occurrence to see tragedies on film, but the ones that are most harrowing are based on true events. Catastrophes seen on the news are often revisited in feature films decades, or even just a few years, after the fact. At their best, these films can serve as tributes. At their worst, they can end up exploitative and inaccurate.

Filmmakers decide whether a tragedy’s portrayal is artistic, mostly nonfiction or with complete historical accuracy, but these choices pose risks. These films can evoke painful memories of loss triggered by what is shown on screen. Filmmakers must take the victims, affected family members and survivors’ wellbeing into account, as well as the effect the film could have on how the tragedy is remembered by the general public.

The over-sensationalized films are often perceived as attempts to make money rather than memorialize the tragic event, such as the 2006 docudrama “World Trade Center.”

“There’s a wonderful old expression: The problem with Hollywood as an art form is that it’s a business, and the problem with Hollywood as a business is that it’s an art form,” said Ron Falzone, an associate professor in Columbia’s Cinema Art and Science Department. “You have those two things battling.”

Hollywood has always had an interest in making these types of movies because people have always had an interest in watching them, according to Steven Lipkin, a professor of Communication at Western Michigan University who has studied docudrama films.

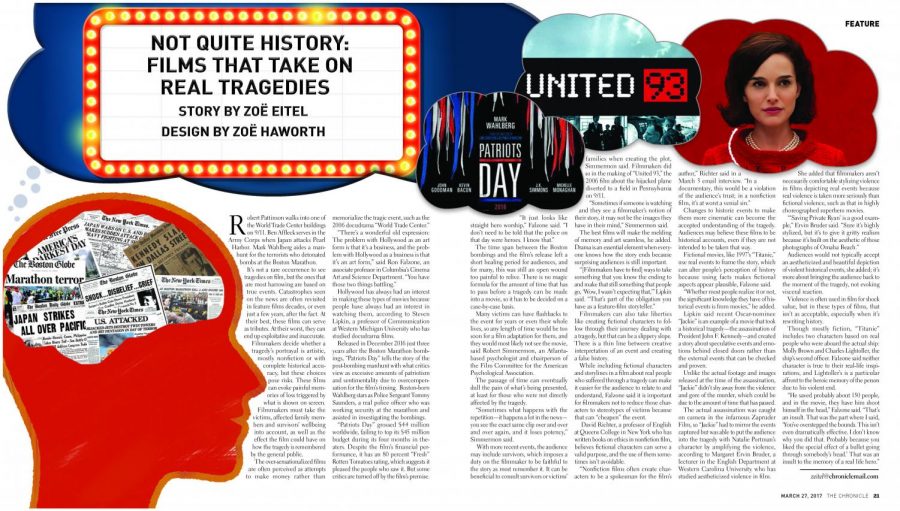

Released in December 2016 just three years after the Boston Marathon bombings, “Patriots Day” tells the story of the post-bombing manhunt with what critics view as excessive amounts of patriotism and sentimentality due to overcompensation for the film’s timing. Boston-born Wahlberg stars as Police Sergeant Tommy Saunders, a real police officer who was working security at the marathon and assisted in investigating the bombings.

“Patriots Day” grossed $44 million worldwide, failing to top its $45 million budget during its four months in theaters. Despite the film’s financial performance, it has an 80 percent “Fresh” Rotten Tomatoes rating, which suggests it pleased the people who saw it. But some critics are turned off by the film’s premise.

“It just looks like straight hero worship,” Falzone said. “I don’t need to be told that the police on that day were heroes. I know that.”

The time span between the Boston bombings and the film’s release left a short healing period for audiences, and for many, this was still an open wound too painful to relive. There is no magic formula for the amount of time that has to pass before a tragedy can be made into a movie, so it has to be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Many victims can have flashbacks to the event for years or even their whole lives, so any length of time would be too soon for a film adaptation for them, and they would most likely not see the movie, said Robert Simmermon, an Atlanta-based psychologist and chairperson of the Film Committee for the American Psychological Association.

The passage of time can eventually dull the pain of what’s being presented, at least for those who were not directly affected by the tragedy.

“Sometimes what happens with the repetition—it happens a lot in the news—you see the exact same clip over and over and over again, and it loses potency,” Simmermon said.

With more recent events, the audience may include survivors, which imposes a duty on the filmmaker to be faithful to the story as most remember it. It can be beneficial to consult survivors or victims’ families when creating the plot, Simmermon said. Filmmakers did so in the making of “United 93,” the 2006 film about the hijacked plane diverted to a field in Pennsylvania on 9/11.

“Sometimes if someone is watching and they see a filmmaker’s notion of their story, it may not be the images they have in their mind,” Simmermon said.

The best films will make the melding of memory and art seamless, he added. Drama is an essential element when everyone knows how the story ends because surprising audiences is still important.

“[Filmmakers have to find] ways to take something that you know the ending to and make that still something that people go, ‘Wow, I wasn’t expecting that,’” Lipkin said. “That’s part of the obligation you have as a feature-film storyteller.”

Filmmakers can also take liberties like creating fictional characters to follow through their journey dealing with a tragedy, but that can be a slippery slope. There is a thin line between creative interpretation of an event and creating a false history.

While including fictional characters and storylines in a film about real people who suffered through a tragedy can make it easier for the audience to relate to and understand, Falzone said it is important for filmmakers not to reduce those characters to stereotypes of victims because that can “cheapen” the event.

David Richter, a professor of English at Queens College in New York who has written books on ethics in nonfiction film, believes fictional characters can serve a valid purpose, and the use of them sometimes isn’t avoidable.

“Nonfiction films often create characters to be a spokesman for the film’s author,” Richter said in a March 3 email interview. “In a documentary, this would be a violation of the audience’s trust; in a nonfiction film, it’s at worst a venial sin.”

Changes to historic events to make them more cinematic can become the accepted understanding of the tragedy. Audiences may believe these films to be historical accounts, even if they are not intended to be taken that way.

Fictional movies, like 1997’s “Titanic,” use real events to frame the story, which can alter people’s perception of history because using facts makes fictional aspects appear plausible, Falzone said.

“Whether most people realize it or not, the significant knowledge they have of historical events is from movies,” he added.

Lipkin said recent Oscar-nominee “Jackie” is an example of a movie that took a historical tragedy—the assassination of President John F. Kennedy—and created a story about speculative events and emotions behind closed doors rather than the external events that can be checked and proven.

Unlike the actual footage and images released at the time of the assassination, “Jackie” didn’t shy away from the violence and gore of the murder, which could be due to the amount of time that has passed.

The actual assassination was caught on camera in the infamous Zapruder Film, so “Jackie” had to mirror the events captured but was able to put the audience into the tragedy with Natalie Portman’s character by amplifying the violence, according to Margaret Ervin Bruder, a lecturer in the English Department at Western Carolina University who has studied aestheticized violence in film.

She added that filmmakers aren’t necessarily comfortable stylizing violence in films depicting real events because real violence is taken more seriously than fictional violence, such as that in highly choreographed superhero movies.

“‘Saving Private Ryan’ is a good example,” Ervin Bruder said. “Sure it’s highly stylized, but it’s to give it gritty realism because it’s built on the aesthetic of those photographs of Omaha Beach.”

Audiences would not typically accept an aestheticized and beautiful depiction of violent historical events, she added; it’s more about bringing the audience back to the moment of the tragedy, not evoking visceral reaction.

Violence is often used in film for shock value, but in these types of films, that isn’t as acceptable, especially when it’s rewriting history.

Though mostly fiction, “Titanic” includes two characters based on real people who were aboard the actual ship: Molly Brown and Charles Lightoller, the ship’s second officer. Falzone said neither character is true to their real-life inspirations, and Lightoller’s is a particular affront to the heroic memory of the person due to his violent end.

“He saved probably about 150 people, and in the movie, they have him shoot himself in the head,” Falzone said. “That’s an insult. That was the part where I said, ‘You’ve overstepped the bounds. This isn’t even dramatically effective. I don’t know why you did that. Probably because you liked the special effect of a bullet going through somebody’s head.’ That was an insult to the memory of a real life hero.”