EDITORIAL: Banning cigarettes is not a solution; dismantling power structures is

EDITORIAL: Banning cigarettes is not a solution; dismantling power structures is

February 15, 2019

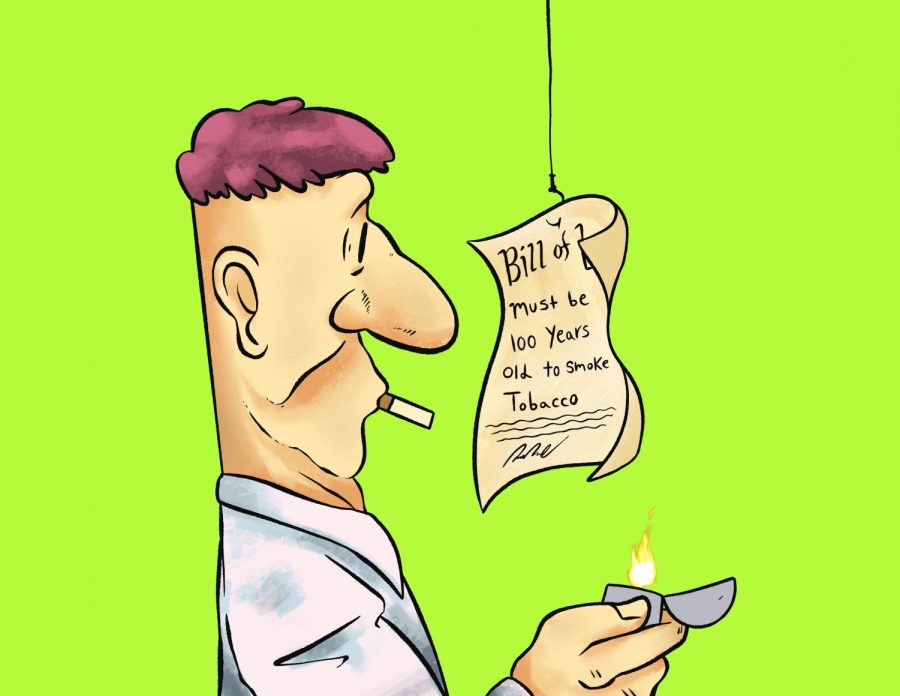

Hawaiian lawmakers introduced a bill raising the legal minimum age to purchase cigarettes. It would go from its current 21 to 30 in 2020, to 40 in 2021, to 50 in 2022, to 60 in 2023, and, finally, to 100 in 2024, effectively banning smoking on the islands. Nationwide, there is a growing push to raise the minimum age to purchase tobacco to 21. Already, six states and about 350 cities, including Chicago, have raised the tobacco purchase age to 21.

Those who push for cigarette bans or age changes have good motivations: health and safety. There are legitimate benefits to reducing the number of people who smoke. But for the government to make the decision for consumers is an overreach. It is not the job of lawmakers to force citizens to live by those policies. Everyone’s body—what they put in it and what they do with it—is their own business. It is not the job of the government to attempt to regulate personal consumption.

Choice must be a core tenet of policy. Removing the choice to smoke may seem like a positive step, but in reality it violates informed consent. Individuals should have access to information about the dangers of smoking and be able to choose whether to undertake the risks.

The push to end smoking is an important fight. However, the focus should be on the kind of positive cultural change that makes smoking unnecessary and obsolete. Campaigns should focus on education and activism, not scare tactics. People who make television and movies should stop glamorizing cigarette smoking. Products that help smokers quit should be affordable and accessible.

The legislation proposed in Hawaii would be nothing more than a band-aid on a bleeding artery. Smoking is not the villain in this situation. According to the Pew Research Center, smoking rates are highest among those who are poor and uneducated. It is not a coincidence that those who are disenfranchised in society are more likely to smoke. If reducing smoking rates is truly an altruistic goal, then the circumstances that turn smoking into a coping mechanism for many must be changed. The downtrodden must be empowered and uplifted.

Removing a small pleasure from the disenfranchised does nothing to improve the quality of life that encourages smoking. Time and money should be spent dismantling structural inequality, not restricting personal freedoms. When structural barriers to education, opportunities and success are removed, individuals will be able to make informed decisions about their own bodies.