New hyperloop train proposal would connect Chicago to Cleveland

March 5, 2018

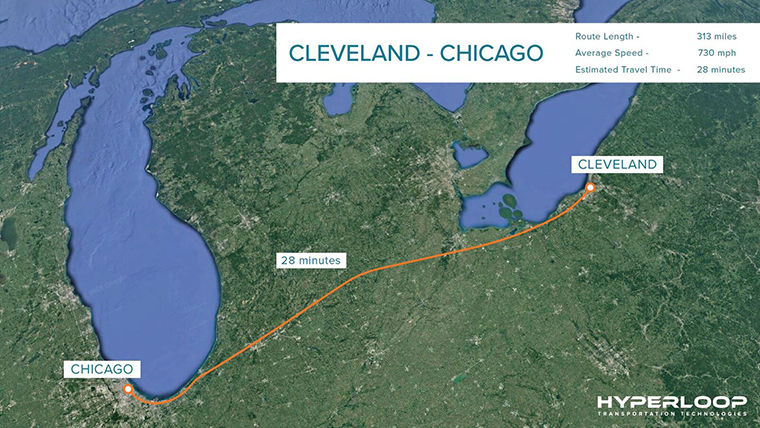

While Chicago is looking at companies to build a proposed O’Hare International Airport–downtown express train, plans are proceeding for a new train that could connect Chicago and Cleveland in less than 30 minutes.

A partnership has been announced between the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency and Hyperloop Transportation Technologies—a Culver City, California-based tech company—for plans to create the Great Lakes Hyperloop. Hyperloop trains differ from conventional trains because they use magnets to move through a series of tubes rather than tracks and wheels, according to the HTT’s website.

NOACA has also signed a memorandum pledging to work alongside the Illinois Department of Transportation to strive toward building the Chicago–Cleveland transit, and the proposed route would be examined in a six-to-nine month regional feasibility study, according to a Feb. 26 HTT press release.

“The Great Lakes megaregion represents a $15 billion transportation market with tens of millions of tons of cargo and millions of passengers connecting to the cities within the region every year,” said Grace Gallucci, executive director of NOACA in the press release. “Technologies like the [Great Lakes] Hyperloop can take our over-stressed infrastructure into the 21st century and beyond.”

Other routes under consideration could connect Chicago to Detroit and cost between $20 million and $45 million per mile.

“Everybody knows [a] high-speed rail is coming, but nobody knows the path we will take to get there,” said Joe Schwieterman, a transportation professor and director of the Chaddick Institute at DePaul University. “Countries around the world are embracing high-speed rail, and the Midwest seems like a logical location.”

The hyperloop would race across the Midwest at an average speed of 730 mph, nearly three times the speed of the world’s fastest train—the Shanghai maglev train in China—which has been clocked at 267 mph.

The region’s flat landscape also makes it ideal for a high-speed transit system as opposed to other mountainous areas in the nation, Schwieterman said. And the terrain between Chicago and Cleveland is as “flat as a pancake,” he added.

The Midwest needs better travel routes to increase access to many major cities across the Midwest such as Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh and others, said Rick Harnish, executive director of the Midwest High Speed Rail Association.

The promise of a 30-minute trip intrigues passengers such as Jordan Gadoury, 19, a sophomore advertising major at Kent State University in Ohio.

Gadoury, a former theatre major at Columbia, said she would endure the “miserable” 6–8 hour bus ride last year from Chicago back to Cleveland about once a month on a Greyhound or megabus.

“If there was a new option of travel out there, I would like to take it,” Gadoury said, adding the hyperloop train’s safety is more of a concern than its high speeds.

While the proposed hyperloop system has drawn excitement from prospective passengers, some transportation experts remain skeptical.

“I would like [to know] what is exciting about it to people,” Harnish said. “People know how to run trains safely and regulate safety. None of that exist for [hyperloop].”

Harnish said he is also uneasy about the limited number of hyperloop trains in operation and thinks states should focus more on high-speed rail transits which have a proven track record. Currently the Shanghai maglev train is the only train that uses magnets to move along the route, similar to a hyperloop, and it has been in operation since 2002.

HTT was unable to comment on the safety procedures or technological implications of the system as of press time.

Schwieterman said trips between 100–350 miles are ideal for high speed train systems. Anything longer and the benefits of air travel would be “overwhelming.”

With the proposed train projected to travel faster than a Boeing 747’s top speed, some experts have their doubts. However, the same doubts could have been said for air travel in the 1920s, Schwieterman said.

“[Hyperloop trains] face long odds, but we are careful not to dismiss [them] because technology is changing so fast,” Schwieterman said.