Saving Chicago’s Youth: In the aftermath of tragic losses, communities create alternative approaches to gang intervention

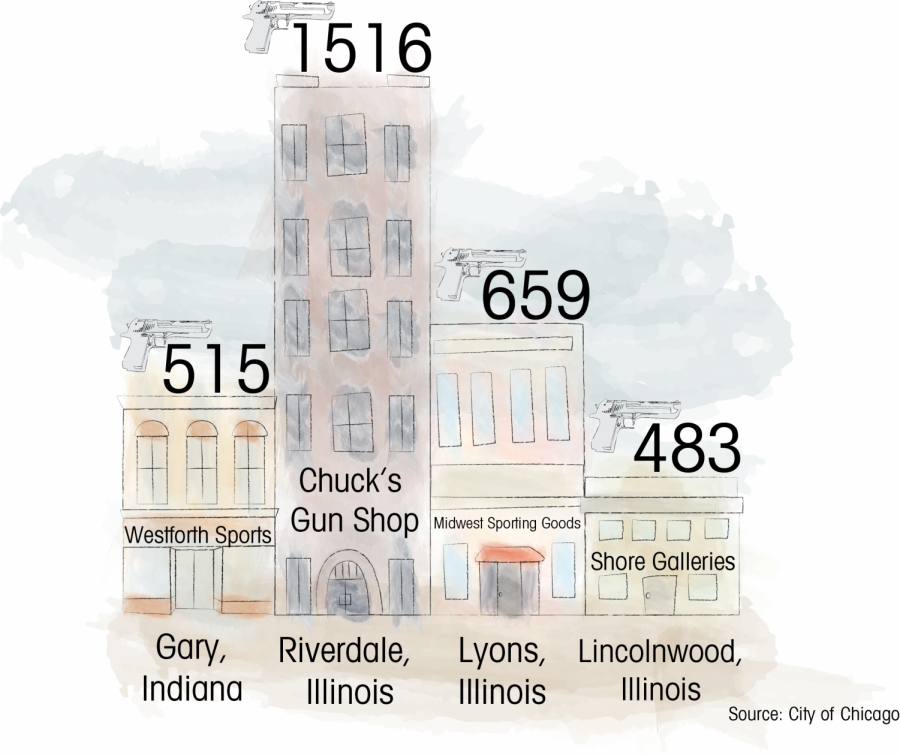

The Chicago Police Department recovered firearms sold from the above gun stores between 2009-2013, making up nearly 20 percent of the illegal firearms used in crimes in Chicago.

November 10, 2014

Wearing a suit jacket, slacks and a blue tie with yellow stripes, Ronald Holt, commander of the Chicago Police Department’s Special Activities Unit, looks like a normal businessman or typical high-ranking cop.

Underneath his dapper attire is a man who copes with the loss of his only son, Blair Holt, to gang violence on May 10, 2007. Ronald Holt now leads the Special Activities Unit—among many other duties—in working with local youth and assisting families affected by gun violence.

Blair Holt, 16, was shot in the upper stomach less than a month before his 17th birthday when a fellow student named Michael Pace aimed at a student with whom he had “beef” while riding the bus from school. Five students were struck, Blair among them. He was gunned down while shielding a friend from the fatal shot.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t think about him [and] wonder what he would be doing now,” Holt said, his loud voice softening. “It’s a daily endurance of emotion, tears every now and again…. I always see kids here and there that remind me of Blair at different stages of his life.”

Holt is not alone in his grief. Though gang-related shootings are reportedly on the decline, they continue to claim the lives of innocent victims such as Blair Holt or Antonio Smith Jr., a 9-year-old honor student from the Greater Grand Crossing neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side who was fatally shot Aug. 20 for reportedly shouting a warning to rival gang members of Pocket Town, a Gangster Disciples faction, according to a Sept. 20 Chicago Tribune report.

But solving the gang violence problem in Chicago is much more complicated than just addressing crime, shootings and gangs. From illegal guns and firearm legislation to fractured family units and education, law enforcement and advocacy groups are addressing Chicago’s complex, long-standing gang violence problems by examining multiple perspectives.

In comparison to declining non-gang related homicides, gang-related homicides declined between 1995–2002 but leveled off between 2001– 2010, illustrating that a greater proportion of all homicides in the city involve members of street gangs, according to a December 2013 study published in the Institution for Social and Policy Studies at Yale University.

According to CPD figures released in March to the Chicago Sun-Times, there were 90 gang-related shootings between Jan. 1 and March 14 of this year, a decline from 163 gang-related shootings during the same three-month period in 2013 and 223 in 2012. However, police statistics were called into question in an April 2014 Chicago Magazine article that detailed how the categorization of the city’s homicides resulted in what appeared to be a decrease in homicides. The police did not provide up-to-date statistics to The Chronicle, as of press time.

It is possible that community outreach is playing a role in the decline in shootings, but homicides will remain stable in troubled communities where members of opposing gang factions share a close space and have intense conflicts with one another, Holt said.

“It’s unfortunate that the homicides continue, but you’re going to get those numbers just about anywhere you go where there’s a dense population of people,” Holt said. “Depending on what they’re fighting over seems so important to them they think that it’s ok to shoot and kill. But it’s not okay to shoot and kill [whether] they’re in a gang or not.”

Within the department’s special activities unit is the Drug Abuse Resistance Education program, in which officers go into schools and educate students on the dangers of joining gangs and abusing drugs, and the Gang Resistance Education and Training program, in which students are taught how to avoid gang violence.

Lloyd Bratz, Regional Director of D.A.R.E. America, who manages programs in states such as Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky, said the new curriculum focuses on helping youth make sound decisions rather than emphasizing the risks and outcomes of their choices, as they did with the program’s past “Just Say No” approach.

“We still talk about risks and consequences, but we also try to prevail on the individual youth to make decisions for himself or herself,” Bratz said.

The police also provide resources for communities, such as information on social service agencies and community support groups for families, finding pastoral care for families and working with the attorney general’s office to generate funding for families of crime victims, Holt said.

The CPD also runs the Officer Friendly program, in which officers visit and build better relationships with students, Holt said, adding that building trust with young people is critical.

The disconnect between law enforcement and youth can happen for several reasons. For young people, it could stem from the perception of police corruption and witnessing mistreatment by the police. For officers, it’s important to understand the communities they serve and not to judge youth based on appearance. Police must be sensitive to the community’s needs.

“They can assume that an African-American boy walking around with his pants sagging [is] up to no good,” Holt said. “In the business of law enforcement, don’t judge a book by its cover.… You get more out of a person when you approach them with respect.”

As for coping with his son’s death, Holt said some days are better than others. He said he still wonders why Pace opened fire that day.

Dealing with the loss of a child is a day-by-day process for any parent, said Angela Rudolph, executive director of the Hadiya Pendleton Foundation, a nonprofit founded by Cleo and Nate Pendleton. Hadiya, their 15-year-old daughter, was fatally shot by alleged gang members a mile from President Obama’s home in a South Side neighborhood shortly after performing with her high school band for Obama’s second inauguration ceremony in January 2012.

Following the loss of their daughter, the Pendletons founded the organization, which advocates for gun control legislation and informs the public on gun violence causes and proper intervention. Through policy work, it aims to address gun violence by supporting tougher gun laws because lax gun regulations are contributing to the city’s violence, Rudolph said.

The CPD confiscates more than seven times as many illegal firearms used in crimes as New York City and double the number of Los Angeles, according to a May 27, 2014, report from the CPD. The largest out-of-state sources of Chicago’s illegal guns were Indiana, Mississippi and Wisconsin, and nearly 20 percent of guns recovered at Chicago crime scenes were purchased at four stores in Lyons, Riverdale and Lincolnwood, all in Illinois, and Gary, Indiana, the report found. Many of the guns coming from these stores have been recovered at crime scenes less than three years after they were bought, according to the report.

The police recovered 515 guns that were sold at Westforth Sports, Inc. in Gary, and 483 sold at Shore Galleries in Lincolnwood between 2009– 2013. During that same period, the police recovered 659 guns purchased at Midwest Sporting Goods in Lyons that were used in crimes in Chicago. Of those, 333—about 51 percent—were confiscated within the years of original purchase at Midwest Sporting Goods, according to the CPD’s report. Chuck’s in Riverdale sold 1,516 guns that were used in crimes in Chicago, 529 of which were recovered within three years of original purchase.

Contrary to popular opinion, not all gang violence is directly targeted at rival gangs, but rather springs from conflicts between individuals that are not necessarily about the gang, Rudolph said. Now that there are more illegal guns in the city, those personal conflicts often result in fatalities.

“If we’re to address the business practices within those said gun stores, [that] could have an immediate impact in terms of the number of illegal guns that are driving what happens in the city of Chicago,” Rudolph said. “Because of the proliferation of guns in our city and our country, typical arguments and fights become deadly because you add guns in the equation.”

Under Illinois’ concealed carry law, those who want to carry a firearm must comply with several rules. They must be at least 21 years old, have a valid Firearm Owners Identification card, complete 16 hours of firearms training, not be prohibited under federal law to possess a firearm and not have any physical violence misdemeanors or alcoholic and drug convictions within the past five years, according to the Illinois State Police Department.

Those escalating interpersonal conflicts—though not all are directly related to advancing the interests of a gang—are more fatal than these of the past, but other factors such as the availability of illegal firearms, quality education and mentorship are also at play, said Roseanna Ander, executive director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab.

Programs that may not be directed toward gang violence prevention but rather focus on education could be an anti-gang strategy, Ander said. As the level of education increases, the probability of crimes like shoplifting, vandalism and assault decrease, according to a study published in the February 2010 issue of Applied Economics.

“We know that … when kids disengage from school, they are at increased risk for all kinds of negative outcomes, including crime and violence,” Ander said. “I think it’s a lot of different things for different kids…. Every case is going to be different, and that requires a system that’s going to be responsive.”

Students begin to lose interest in school for a variety of reasons, such as trauma and other unmet mental health needs resulting from the violence within their communities, trouble at home or falling behind in their coursework, Ander said. For example, once students have fallen behind in their math courses, that can become a barrier to getting their diploma, but having a tutor and mentor can help those students catch up, she said.

“How can we figure out how to remove that barrier and help kids—even when they’re far behind—learn the material and get past the math class so that they can stay on track or get on track to get a high school diploma?” Ander said. “I think [we should not be] giving up on kids— which people are too willing to do once they’re a teenager—and say instead, ‘What are the things that work best, and how do we take those things to scale?’”

Education can be a critical part of reaching out to youth, but having a mentor to relate to helps reinforce the necessity for education and thus deters kids from resorting to joining gangs.

When Diane Latiker, mother of eight and founder of Kids Off the Block, reaches out to kids and teens, she lets them know she is there to help them but stresses that their choices will shape their futures.

A resident of the Roseland neighborhood, she said she listens to them describe a variety of problems such as homelessness, lack of a father figure, grandparents stepping in as parents, falling behind in school and living in fear of the gangs.

After hearing her children’s friends discussing gang violence in the community, she decided in July 2003 to found Kids Off the Block, a nonprofit youth program that helps kids and teens with education, health and life. She said she has seen kids who have gone on to receive higher education while others, despite her reaching out to them, fell into gang life. Latiker said some of her mentees have lost their lives to gang violence.

“Some of them have told me, ‘I won’t live to see 20, so why should I think about it?’” Latiker said. “[When they join a gang] I’m very hurt, and I criticize myself for not doing enough…. I so want them to see what I see in them.”

The children and teenagers in her organization have witnessed violence in their communities, lived with broken families or dealt with issues in school. With a broken home life, joining a gang can fill the void and provide a sense of family.

“They join gangs because their families are so broken up,” Latiker said. “The gang is a negative family … but it’s a family and they feel like they belong, and it’s better than what’s at home.”

For Alex Del Toro, a father, the program director of Safety and Violence Prevention for the Humboldt Park and Logan Square YMCA and a former gang member, the lack of a father figure in a family with no brothers and three sisters was a major factor in his decision to join a gang. Making fast money within the safety of his neighborhood was also another benefit, he said. With a hard-working single mom and a dad he never met, leaders of the local street gangs he leaned on when he began gangbanging at about 9 or 10 years old, he said, adding that the streets are hard to compete with when pulling kids away from gang life.

“When I saw these guys on the street, I wanted that acceptance and that unconditional love,” Del Toro said. “The streets are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, and that’s hard to compete with because you can’t go up to a young person and ask them to give up the streets without giving them something in return.”

In addition to keeping up with them while in school, at home and at the center, the YMCA has a variety of programs that engage kids with different interests, Del Toro said.

When he was in school, he was on the varsity football team but was asked to leave after rival gang members opened fire at him during a game, pushing him further away from school and into the street life.

When reaching out to at-risk kids, Del Toro said he talks to them using street language, stays in their lives as long as he can and tries to convince them to dream bigger than their neighborhood.

He said the YMCA’s mentors go into neighborhoods and try to attract kids to their programs, but keeping them interested is not easy. In some cases, a kid will be born into a family that has been involved in gang activity for several generations, but in the end, he tries to teach young people to aspire to see the world beyond their neighborhood, Del Toro said.

“You’re looking for the people who know it’s time to go [because] this isn’t worth [their] life,” Del Toro said. “If I can convince that kid that there’s more to life than the four corners, and he believes and buys into [that] what his family and all these other people think is irrelevant, now you’ve got a dreamer.”

When teachers, parents or other authority figures talk to young people without knowing much about gang life, it can encourage them to find acceptance on the streets, he said, adding that people join for reasons like protection, fear or family tradition.

Ultimately, Del Toro’s children were his motivation to leave the gang. He said he preferred not to disclose the set with which he identified. He did not want his children to grow up without a father like he did.

“My kids saved my life, ’cause their existence is what made me want to leave the streets,” Del Toro said. “I’m going to be Alex, now…. No more selling drugs. No more giving people commands to hurt [other] people. I’m going to go out there, and I’m going to do this for my kids.”