Michael Rabiger, a pioneering documentary filmmaker whose textbooks and teaching shaped generations of nonfiction filmmakers and who co-founded Columbia’s film and video program, died June 8 at his home in Chicago. He was 86.

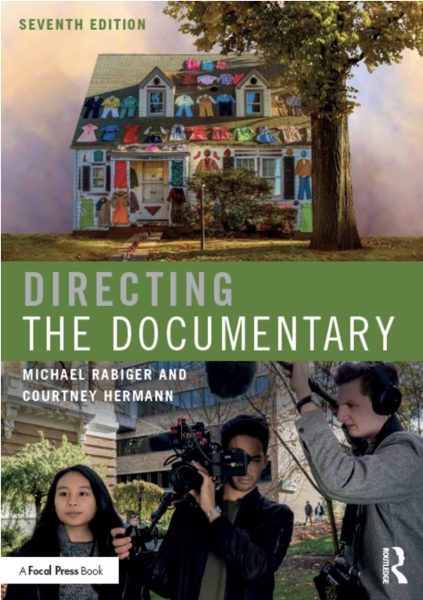

Rabiger was best known for authoring “Directing the Documentary,” a foundational text now in its 7th edition, widely used in film schools around the world. First published in the late 1980s, the book emphasized experiential learning and storytelling ethics in documentary practice. His follow-up, “Directing: Film Techniques and Aesthetics,” became another classroom mainstay.

“Film is the preeminent form for examining the world we live in,” Rabiger once wrote. “The great mirror we try to hold up to everything that matters.”

In more than three decades at Columbia, he helped build what became one of the country’s largest film schools, mentoring students and establishing the college’s Documentary Center, which now bears his name.

Born Jan. 3, 1939, in England, Rabiger entered the British film industry at 17, working as an assistant editor at Pinewood and Shepperton Studios. He later edited more than 30 television documentaries for the BBC, Granada Television and other European broadcasters. From 1967 to 1972, he directed 21 BBC documentaries in six countries, many focused on oral histories and social themes.

As budget cuts and labor unrest rocked the BBC, Rabiger looked abroad. In 1972, during a chance meeting in London with filmmaker Robert Edmonds, who was chair of Columbia’s then film department, he was invited to join the small, developing unit. He immigrated to the United States and began teaching that fall.

At the time, Columbia’s film program had only 60 students. Working alongside colleague Tony Loeb, Rabiger helped restore equipment, build facilities and shape a philosophy of instruction grounded in practical filmmaking and creative exploration. In 1988, he launched the Documentary Center, creating a hub within the college and the broader community.

“Tony Loeb was the chairman when Michael and Chap Freeman joined the Film Department,” said Rabiger’s wife, Nancy Mattei. “All three of them developed the curriculum and the philosophic foundation.”

Rabiger was a frequent lecturer internationally, leading workshops in Jerusalem, Berlin, Cuba, Denmark and Mexico City, among others. He also taught at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and collaborated with CILECT, the international association of film schools, to shape global film education.

He was named chair of Columbia’s film and video department in 1996. Four years later, he published “Developing Story Ideas,” a guide to ideation and narrative structure for aspiring filmmakers.

In 2001, Rabiger retired to focus on writing, though his presence remained central to Columbia’s film community. He was named professor emeritus in 2005, and the same year received the Genius Career Achievement Award from the Chicago International Documentary Festival. His other honors included the Preservation and Scholarship Award from the International Documentary Association and an honorary professorship at the University of Buenos Aires.

“He taught us how to bear witness to the hard realities of life—refusing to believe that there is only one dominant narrative,” said former graduate student Suree Towfighnia, a documentary filmmaker and now an assistant professor at the Metropolitan State University of Denver.

She said that his impact on Columbia was immeasurable, as he created a community in the film and video department that was centered on community and collaboration. “I work to embody his generosity in my classes,” Towfighnia said, “To be a source of light to the next generation and to offer hope and remind them that their stories matter too.”

Ted Hardin, an associate professor at Columbia, said Rabiger had a gift for creating “story connections between the teacher and student, documentary maker and subject, and individual and the world.”

“Michael believed that every person doing anything creative has a potential contribution to make, and it’s either to the collaborative team, to the process, to the story itself,” he said.

Courtney Hermann, a Columbia alum, worked closely with Rabiger the last few years and co-wrote the 7th edition of “Directing the Documentary,” which came out in 2020. The 8th edition is currently in progress, Hermann told the Chronicle.

“I was struck by Michael’s humanistic approach to art and life—an approach that resonates now more than ever,” said Hermann, a filmmaker and associate professor of film at Portland State University.

Rabiger was a frequent visitor and guest lecturer at Columbia even after he retired, attending screenings and celebrating the achievements of film faculty and students. Although his documentary center remains at 1104 S. Wabash building, five of the college’s full-time documentary film faculty were laid off earlier this year in a historic restructuring at the college to address declining enrollment and a financial deficit.

The film and video program he helped build is now part of the School of Cinema and Television and is the largest at the college, even as overall enrollment has declined. In 2020, there were more than 1,000 film and television majors, according to the Office of Institutional Effectiveness. In 2024, that number declined to 741, but the numbers of students in the BFA increased, from 72 in 2020 to 246 in 2024.

In a 1998 interview for Columbia’s oral history project, Rabiger described his first years at Columbia College and some of the challenges as the college grew. “Columbia’s always been an interesting place,” he said. “We’ve had a great deal of freedom, from being fettered by an administration that wanted to dictate what we taught and how we taught it, we had a great deal of trust placed in us.”

In the second edition of “Developing Story Ideas” published in October 2005, Rabiger included a foreword dedicated to his wife whom he married in 1975. “My toughest critic is my wife, Nancy Mattei. I offer her my heartfelt appreciation for her contributions to my work and for putting up so gracefully with a writer’s antisocial work habits,” he wrote.

Rabiger died at the home he shared with Mattei in the North Park neighborhood of Chicago. He had three children from his first marriage to Sigrid Baer.

“Even in his final months, Michael remained committed to reinvention,” Hermann said. “The world is worse without him in it but better for his having been here.”

A memorial service is being planned, Mattei told the Chronicle, but no details were available at the time of publication.

Copy edited by Kate Larroder and Vanessa Orozco