Senior acting major Kamiyah Castellanos is observing her first Ramadan in on-campus housing at the University Center. She is on a meal plan but because she fasts and needs to eat outside of the regular dining hours, she relies on grab-and-go meals from the dining hall.

At the start of Ramadan, Castellanos had no idea the dining hall offered premade meals available to residents for Ramadan because the University Center didn’t let students know of the special service until nearly a week into the holy month for Muslims.

She and other Muslim students at Columbia said the college doesn’t do a good job of communicating what resources are available to them.

Christina Walker, a first-year ASL interpreting major and student crew member at the Student Center, said the reflection space is supposed to be unlocked for the hours the building is open from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. on weekdays and 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. on Saturday.

However, several students told the Chronicle the space has been locked during those times.

First-year music composition major Mohammed Ibrahim, who found the door locked when he tried to use it for his evening prayer, said he prefers the space since he doesn’t want “prying eyes” on him.

Student Student Director Lauren Nazarian declined to comment until she had more information.

This year, the Islamic holy month started after sunset on Feb. 28 and lasts through March 29. For Muslims, this is a time for prayer, communal gatherings and fasting from food and drinks from sunrise to sunset. Many try to be with others for a predawn meal, called suhoor, or for iftar when they break their fast at the end of the day.

On March 6, six days into Ramadan, the University Center, the multi-college dormitory housing for Columbia, DePaul University, American Academy, Roosevelt University and National Louis University, sent an email notifying residents of alternative meal options for those who are fasting during the day.

This was a day after the Chronicle asked if special meals or accommodations were available to Muslim students. However, Ro Jamsetjee, director of housing of PeakMade Real Estate, which owns the University Center, said the property managers have been offering the to-go meals since March 3, even though the email was sent three days later.

Jamsetjee said this delayed notice was because they needed more time to “work out the minor logistics,” and to ensure that the meals wouldn’t be taken by other residents who didn’t need them.

According to Jamsetjee, the meal exchange program started during Ramadan in 2019 when students were asked to inform the University Center the morning of the day that they wanted a to-go meal. However, some students weren’t able to notify them in time to receive their food. Now, students “can come at their convenience,” she said. The meals are offered at the Market, a small convenience store and cafe next to the Caf, the buffet-style dining hall in the University Center. On weekdays, the Market is open from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. and from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. on the weekend.

The Caf is open 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Friday with two to three hour breaks when shifting breakfast, lunch and dinner options. On the weekend, it is open from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

On Wednesday, March 12, sunrise in Chicago was at 5:52 a.m., with iftar beginning at sunset at 6:53 p.m. By the end of Ramadan, sunset will occur after 7 p.m.

According to the email about the Ramdan meals sent to residents, students need to complete a “Ramadan Meal Exchange” form with the cashier each time.

The University Center currently has four residents signed up for the meal exchange but carry extra suhoor and iftar grab-and-go meals in preparation of additional guests and students, said Brooke Lopeman, the director of university relations at PeakMade Real Estate. In total, the University Center will have 12 to 14 iftar meals prepared daily, but only eight of them are taken each day on average, she said.

Before the email from the University Center, Castellanos had difficulty finding meal options in the UC dining hall during sundown because pork was an abundant option that she could not eat, even mixed into the vegetables on one occasion, she said.

“It’s kind of difficult to navigate, because nobody wants to have chicken tenders, burgers and hot dogs every day, just because they can’t have what’s being served regularly,” Castellanos said.

The Ramadan to-go bags have halal butter chicken and vegetarian options like chana masala or palak paneer for dinner. For the predawn meal, they have lighter foods like hard boiled eggs, dates, overnight oats and yogurt or dairy free alternatives.

Jamsetjee said that the premade meals have been provided by Asiana of Foodville for the past six years with a pause during the pandemic. The meal exchange allows students observing Ramadan to take two meals at a time: one for when they break their fast and another for their meal before sunrise the next day.

Even students who don’t live in the dorms said scheduling time for iftar can be challenging, alongside their classes and other workloads. Some have noticed that the college hasn’t mentioned that it’s the start of Ramadan. Other Chicago universities offer iftar dinners and campuswide Eid celebrations at the end of Ramadan.

Columbia could do more, “even if it’s in a brief email at the beginning of Ramadan, like ‘Happy Ramadan, here is something we have available to students,’” said Shaymaa Atwa, a junior creative writing major.

During the first week of Ramadan, Atwa was in an evening class when the sun set. She said she felt “awkward” eating in class or leaving for a snack without explicit permission from her professor.

“I broke my fast with water, but you can’t really sit and eat in class, so I wasn’t really sure what to do that day,” Atwa said.

As she hasn’t heard any faculty members mention Ramadan in class, Atwa said that it would be nice to know if students were allowed to step out for a snack or have something small to eat without it being a disruption.

Ibrahim, who is medically exempt from fasting, said that he will miss a prayer time if he has a class during and wait until after. While he could ask his professor for five to eight minutes to step out of the room to pray like he did his first semester, he doesn’t want it to be “at the expense of potentially missing information,” he said.

During his “Foundations of Music I” course, Ibrahim had to excuse himself to pray. He said he got “extremely screwed over” due to missing out on “one little important detail,” which affected him later.

“It is impossible in the day-to-day life on campus to properly meet those needs,” Ibrahim said. “I guess it’s a common struggle with other Muslim Americans like me.”

Ibrahim misses having a community, especially after the Muslim Student Association disbanded this school year after its leadership graduated in May 2024.

“It’s already enough trying to practice our faith in an environment that’s really the stark contrast and not even having at least some sort of community,” he said. “The least the school can do is make it easier, for example, leaving the prayer room unlocked for longer times.”

Sarah Hasany, senior fashion studies major, “loves” the prayer space but has also recently encountered the locked door upon her daily visit.

“It’s a great space,” she said. “I’ve been having some issues there recently, because they seem to be locking the space up a lot, and it’s been kind of hard to access sometimes.”

Atwa said she never knew of this designated space, and encouraged more promotion of it to other students who might want to use the room.

Hasany, also a former board member of MSA, also found it important to raise recognition among the school.

“Giving some awareness to the staff, as just a heads up of ‘Hey, some of your Muslim students may be practicing Ramadan, and they’ll be fasting all day. So, just be mindful of that and give them some grace.’ It would be nice if the school had said something like that,” Hasany said.

Atwa said this Ramadan has been hard since it’s the first time she’s been away from family during the holy month.

“I have rarely seen any other Muslims on campus, so it feels like a very, very small community,” Atwa said. “It’s harder to get to know anyone else.”

Hasany said after the MSA founders graduated, the board found it difficult to pass the baton onto new students, leading to its inactivity this academic year. She said though a restart is in the works, the club’s absence this year was felt by the Columbia Muslim community.

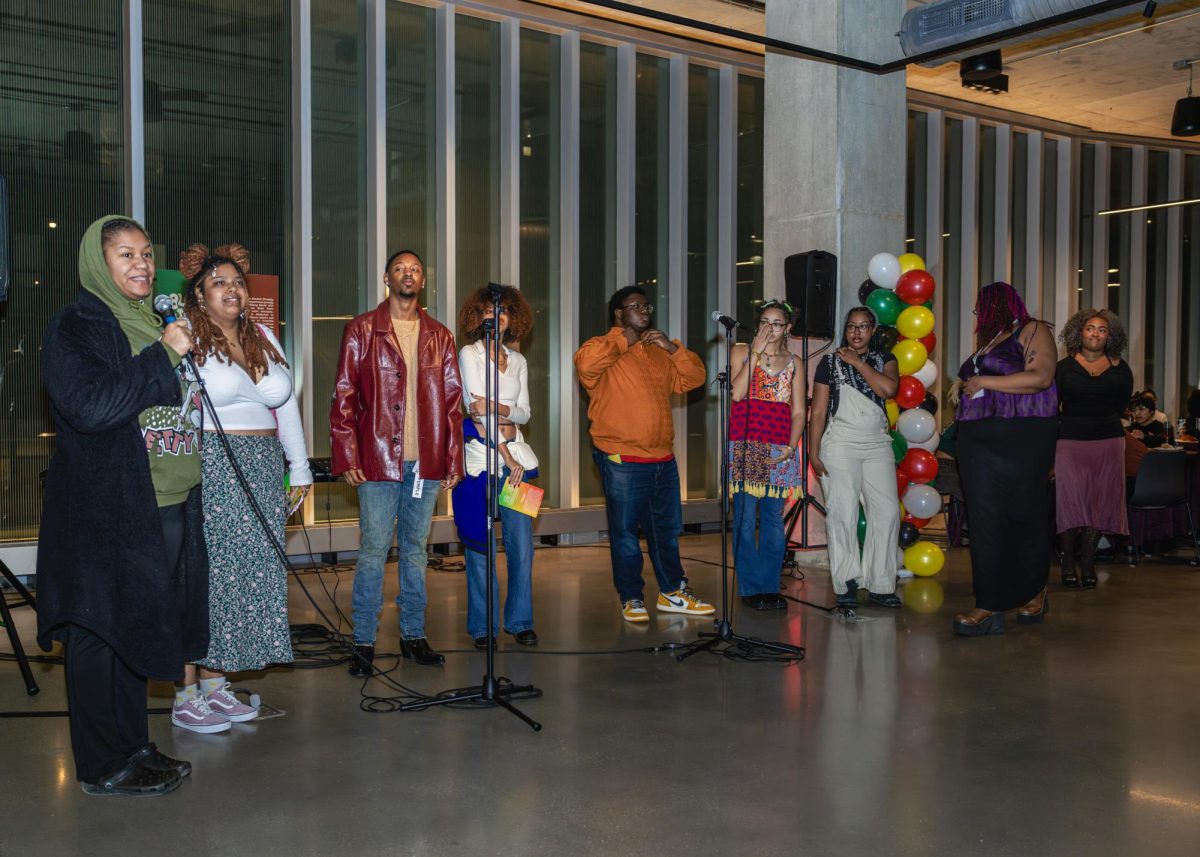

“I feel like that is one thing that has been kind of sad about this specific year, is the lack of feeling the community spirit on campus,” she said. “Every year, we had a Ramadan iftar party, which is basically a party when we break our fast. It would be a community event, it was typically a potluck, and that’s something that we don’t have this year, which is actually really sad.”

Ibrahim has also felt the lack of community and resources during this Ramadan. Without MSA or an available community on campus, Ibrahim said this first year at Columbia feels “rather isolating.”

“At this college, finding a Muslim here is like finding a needle in a haystack,” he said.

Copy edited by Trinity Balboa

Resumen en Español:

Los estudiantes musulmanes de Columbia expresaron sentimientos de frustración, por la falta de recursos en campus para ellos durante el Ramadán. Les cuesta encontrar una comunidad, por incidentes como un aviso retrasado de las comidas para llevar, que los estudiantes llevan para comer al empezar al anochezer, un espacio cerrado de reflexión, utilizado para rezar y meditar y la discontinuación de la Associación de los Estudiantes Musulmanes.

Resumen por Sofía Oyarzún

Texto editado por Doreen Abril Albuerne Rodriguez